A Foretaste of Glory Divine by Maxie Dunnam

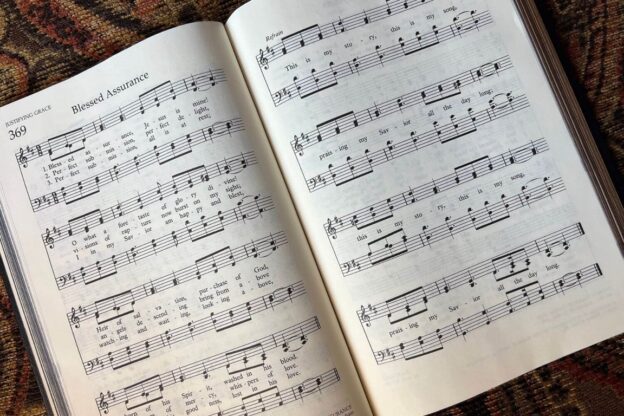

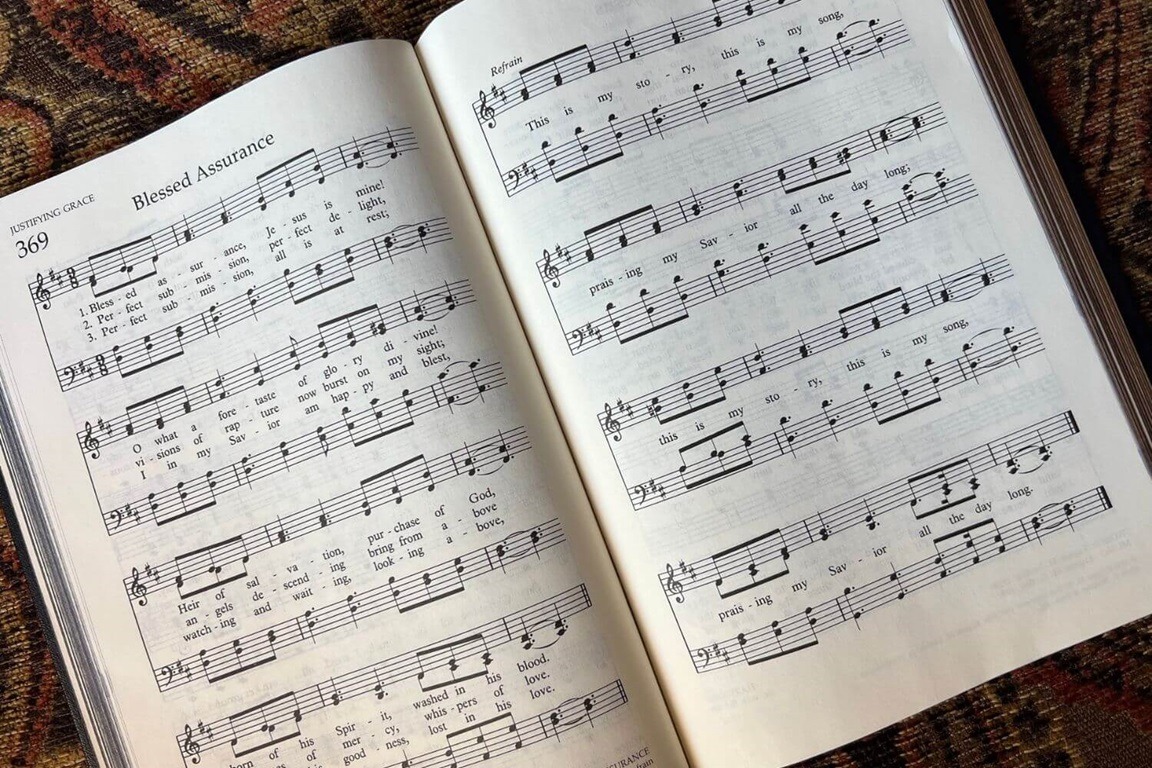

Singing is one of our greatest expressions in the Christian faith and way, especially in the Wesleyan/Methodist tradition. We sing our faith.

One of the hymns we sing often is Blessed Assurance. The hymn is emotionally overwhelming when we know about the author, Fanny Crosby. From six weeks of age until her death shortly before her 95th birthday… Fanny was blind. Sadly, the blindness was caused by a medical error when a doctor put mustard poultice on her inflamed eyes from a cold infection… resulting in immediate blindness.

Her widowed mother and grandmother even took her to the famous New York surgeon, Dr. Valentine Mott, but it was too late…the damage was permanent. He was heard to lament as they left the examining room, “Poor little blind girl.” However, Fanny never saw her affliction as anything but a blessing. When she was eight years old she wrote this simple little verse:

Oh, what a happy child I am

Although I cannot see

I am resolved that in this world

Contented I will be.

No wonder the first stanza of her hymn, Blessed Assurance, underscores assurance as “a foretaste of glory divine.” She had only words, but I don’t know anyone who has used words with greater depth of feeling. Pause a moment to relish it: a foretaste of glory divine.

In our Methodist/Wesleyan tradition, assurance of salvation is one of the four “all” convictions about salvation: all need to be saved; all can be saved; all can know they are saved; all can be saved to the uttermost.

It may be my age, but let’s not lodge it there. The third “all” is life giving: all can know they are saved. There are few experiences that can provide more power in our lives than to have assurance of our salvation. Think what it could do for any one of us:

- Our timidity and uncertainty about witnessing would be dissolved. We would not be intimidated by those “buttonhole” witnesses who come on like gangbusters. We would know that tenderness, patience, and understanding are authentic testimonies, as well as words.

- We would not get overwrought with our Christian friends who insist on future security, for we would be assured of our present relationship with Christ.

- We would be joyous in our service for God, but not in our works, or mistaken in the notion that our works save us.

- We would be delivered from frantic preoccupation with minute by minute temperature taking because we could relax in our trust in the Lord.

And all of that would help every one of us, wouldn’t it?

Blessed Assurance …Oh what “a foretaste of glory divine.”

Subscribe

Get articles about mission, evangelism, leadership, discipleship and prayer delivered directly to your inbox – for free