Scripture Focus:

In the days when the judges ruled in Israel, a severe famine came upon the land. So a man from Bethlehem in Judah left his home and went to live in the country of Moab, taking his wife and two sons with him. The man’s name was Elimelech, and his wife was Naomi. Their two sons were Mahlon and Kilion. They were Ephrathites from Bethlehem in the land of Judah. And when they reached Moab, they settled there. Then Elimelech died, and Naomi was left with her two sons. The two sons married Moabite women. One married a woman named Orpah, and the other a woman named Ruth. But about ten years later, both Mahlon and Kilion died. This left Naomi alone, without her two sons or her husband.

Then Naomi heard in Moab that the Lord had blessed his people in Judah by giving them good crops again. So Naomi and her daughters-in-law got ready to leave Moab to return to her homeland. With her two daughters-in-law she set out from the place where she had been living, and they took the road that would lead them back to Judah. But on the way, Naomi said to her two daughters-in-law, “Go back to your mothers’ homes. And may the Lord reward you for your kindness to your husbands and to me. May the Lord bless you with the security of another marriage.” Then she kissed them good-bye, and they all broke down and wept. “No,” they said. “We want to go with you to your people.” But Naomi replied, “Why should you go on with me? Can I still give birth to other sons who could grow up to be your husbands?”

And again they wept together, and Orpah kissed her mother-in-law good-bye. But Ruth clung tightly to Naomi. “Look,” Naomi said to her, “your sister-in-law has gone back to her people and to her gods. You should do the same.” But Ruth replied, “Don’t ask me to leave you and turn back. Wherever you go, I will go; wherever you live, I will live. Your people will be my people, and your God will be my God. Wherever you die, I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord punish me severely if I allow anything but death to separate us!” When Naomi saw that Ruth was determined to go with her, she said nothing more. So the two of them continued on their journey.

Ruth 1:1-11, 14-19 (NLT)

We’re concluding our focus on temperance by taking another look at the story of Naomi, Ruth, and Orpah. Remember where we left off last week – both Ruth and Orpah face a very difficult decision. As the three women stand on the road, tears abound and both Ruth and Orpah are deeply torn and heartbroken over the prospect of leaving Naomi. After much crying and sorrow, Orpah makes the very logical and rational choice to return to the safety of her family while Ruth chooses to follow Naomi to a foreign land.

Remember also how precarious it was for widows in Bible times – especially those who did not have family or who were in a foreign land. It was perfectly acceptable to turn your back on them completely.

So Ruth followed but Orpah did not. The contrast between these two choices reflect the tension that exists with many of the choices we face throughout our lives. As we mentioned last week, all of our choices are important, even the small ones, because they are intertwined with our faith. The nature of our faith will determine the decisions we make about our commitments, and the decisions we make about our commitments will determine the nature of our faith.

The problem is that many people want to paint our choices as being clearcut and having only one right answer. There will always be people out there who believe we all need to be Ruths and there will be others who believe we all need to be Orpahs. And this isn’t simply an issue for women. It’s true for all of us and in all areas of our life.

Two areas in particular exemplify the extreme way we’re forced to make our life choices – the areas of home and work. In these areas, many of our cultures have created two false and competing choices and have offered these up as our only one. Both of these are extremes. The first is if you want it, you have to sacrifice everything else to get it. This false choice has been offered to both men and women – especially in western cultures.

For men, it’s a dilemma they have always faced. Work has been and continues to be seen as the main and sometimes only source of meaning and identity for men. It’s the place where they’re supposed to find fulfillment and gratification. They’ve often found themselves burdened with the sole responsibility for protecting and providing for their families and being a “good man” is often judged on how well they perform in the arena of work. Other arenas of life, particularly home and family, have never been fully validated as appropriate places for men to turn for inner contentment and satisfaction. Thankfully, this is changing with younger generations, but the false choice still remains strong.

In the 1970’s this “all or nothing” emphasis became a rallying cry for many women as well. There was a push for women to catch up with men in the workplace. This push included the subtle message that the pursuit a career included denying the validity of a woman’s ties to home and family. Again, an extreme and false choice.

A second false choice was offered primarily to women in my generation who came of age in the 1980’s. It was a boomerang to the extreme of Superwoman. Women were told that they could be a supermom and a super career woman all at the same time. Rather than an “all or nothing” mentality, this was a “you can have it all” understanding.

The reality, however, is that both of these extremes are false choices. Our lives are not like that. It may be possible for both men and women to work without sacrificing everything or denying their ties to home; but it’s also true that we can’t do everything without making some sacrifices. There will also be times when our commitments clash. More importantly, the issue of balance can’t be neatly divided into the categories of work and home. We need balance across all areas of our lives.

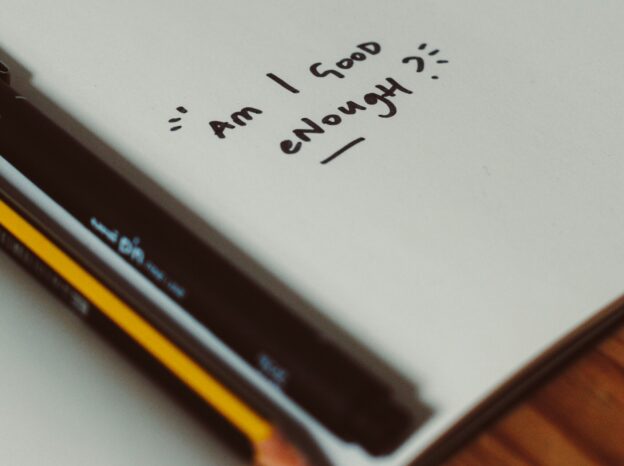

The fact that life is filled with conflicting commitments points to the necessity of temperance. If we are to apply the virtue of temperance to our life, we must grasp the concept of “good enough.” “Good enough” is an idea that desperately needs to be rediscovered. We’re encouraged by society and even by Scripture to pursue excellence. Paul tells the Philippians, “if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.” (Phil. 4:8). There is nothing wrong with striving to be the best you can be. I believe excellence is a noble aspiration; but I also know that it can be damaging as well. Many families have suffered at the hands of a workaholic striving to be the best employee there is. So there is a place for the notion of “good enough.”

When I first started seminary, I felt extremely stressed. I couldn’t seem to find the right rhythm. Used to excellent grades and hard work, I naturally immediately reverted to my old study habits and expectations; but somehow it just didn’t work the way it had in college. What I failed to realize was that my life was different than when I was in college. I was married, had a baby, and my husband was gone most of the time because of the demands of his surgical residency. I quickly discovered I wasn’t going to be able to be at the top of my class and be able to give my son, Nathan, the attention he needed. At the same time, I also recognized I wasn’t going to be able to be the “ideal” mother I had envisioned myself to be and successfully complete my master’s degree. I had to find a balance. I had to find a way to be a good enough seminary student and a good enough mother. I had to accept that being good enough at both those things was okay. Ironically, what I discovered was when I recognized the value of being good enough, I found my rhythm, regained my balance, and began to excel both at home and at school.

Orpah knew about good enough. She made a decision, albeit a painful one, that was good enough for her. Each of us can claim that for ourselves as well. This isn’t just a “woman thing” either. All people need to claim “good enough.” Rather than being torn in a million different directions, we need to make decisions that help us become good enough mothers and good enough fathers, good enough children and good enough siblings, good enough employees and good enough volunteers, good enough friends and good enough citizens. When we find the balance of good enough, temperance reigns in our lives and we are free to excel.

As you pray and fast, I pray that you will discover the decisions and adjustments you may need to make in order to be “good enough” rather than succumbing to the pressure to be “super.” And that this discover will open you to newfound balance in which you are free to excel.