Foundations Of Disciple-Making: Friendship by Paulo Lopes

In March of 2020, as many of us were coming to terms with the COVID-19 pandemic, I became close friends with a neighbor. Our kids are close in age, and we defiantly kept a similar “open-door policy” with our neighbors and their kids in a season when many were understandably afraid of contagion (or peer-judgment). Because of our likeminded attitude towards what was going on in that messy season, Greg and I ended up spending quite a bit of time together. We started going on walks, then later began working out together in the garage. Our wives and kids got along, so soon enough we were doing game-nights at each other’s houses and even scheduling family trips together. Greg and his family might not know this, but their friendship was a huge blessing to us in a season of uncertainty, work transitions, and even relational turmoil.

If you are picking up this thread for the first time, it may be helpful to read the first four parts of this five-part series on “The Foundations of Disciple-Making.” Throughout this series, we have explored five foundational elements, arguing first that disciple-making is, at its core, about relationships, builds through experience, needs access, and thrives with mutual admiration. If you are joining partway through, you may find it helpful to begin with Part One. Recalling these steps, we move to our final reflection on friendship.

The Power of Peer Discipleship

An odd feature of being in full-time ministry is a perception that because I’m “the professional Christian” in the relationship, I’m responsible for leading all the faith or discipleship related conversations. It’s a common yet detrimental misperception that, I believe, comes from our desire to model ministry after the likes of Paul and Jesus himself. We see the way Jesus taught, corrected, challenged, and admonished his disciples and we automatically think “that’s how I need to do it too.” Later in the New Testament we read Paul’s instructions to the many churches he planted, or even his father-like relationship with Timothy, and we conclude it’s the best model for disciple-making.

Christian Leadership vs. Friendship: Understanding Roles in Discipleship

Now, we’ve established already in this series that there’s nothing wrong with seeing Paul as a model, much less Jesus, who, after all, is the one who commanded us to make disciples! Additionally, we agree that the whole point of discipleship should be that persons become more like Jesus. So, what’s the issue then? Well, if we’re not careful, we miss a necessary differentiation between our personal involvement in disciple-making through intentional relationships, and specific roles we might play for the sake of the people of God. This is an important differentiation because roles-based relationships are asymmetrical. In other words, in roles-based relationships, one person holds authority or power over another, like a teacher, a shepherd, a leader, etc.

Most of the examples we find in Jesus’ ministry, as well as in Paul’s writings to churches, reflect asymmetrical relationships to certain extents. Paul was an apostle. He planted most of the churches he is writing to. Notice how he often spends time establishing authority by listing his hardships for the sake of the Gospel (2 Cor 11:23-28), articulating his Divine calling (Gal 1:1), or even his claim to have “seen Jesus Christ our Lord” (1 Cor 9:1). In short, those churches were reading Paul’s letters because they came with embedded authority. Yes, it was relational. Yes, there was friendship. However, they were not on equal footing.

The same goes for Jesus. Why? Well, because he is Jesus! And, while Jesus made a point of even using the word “friend,” the reality is that it would be a stretch to try to establish parity or equity in the relationship between him and his disciples. Once again, it is absolutely true that Jesus considered his disciples to be friends, but he also called them children. One thing doesn’t negate the other. It’s just important to realize that there are relationships, and there are roles. Making sure we understand the difference is key to healthy disciple-making.

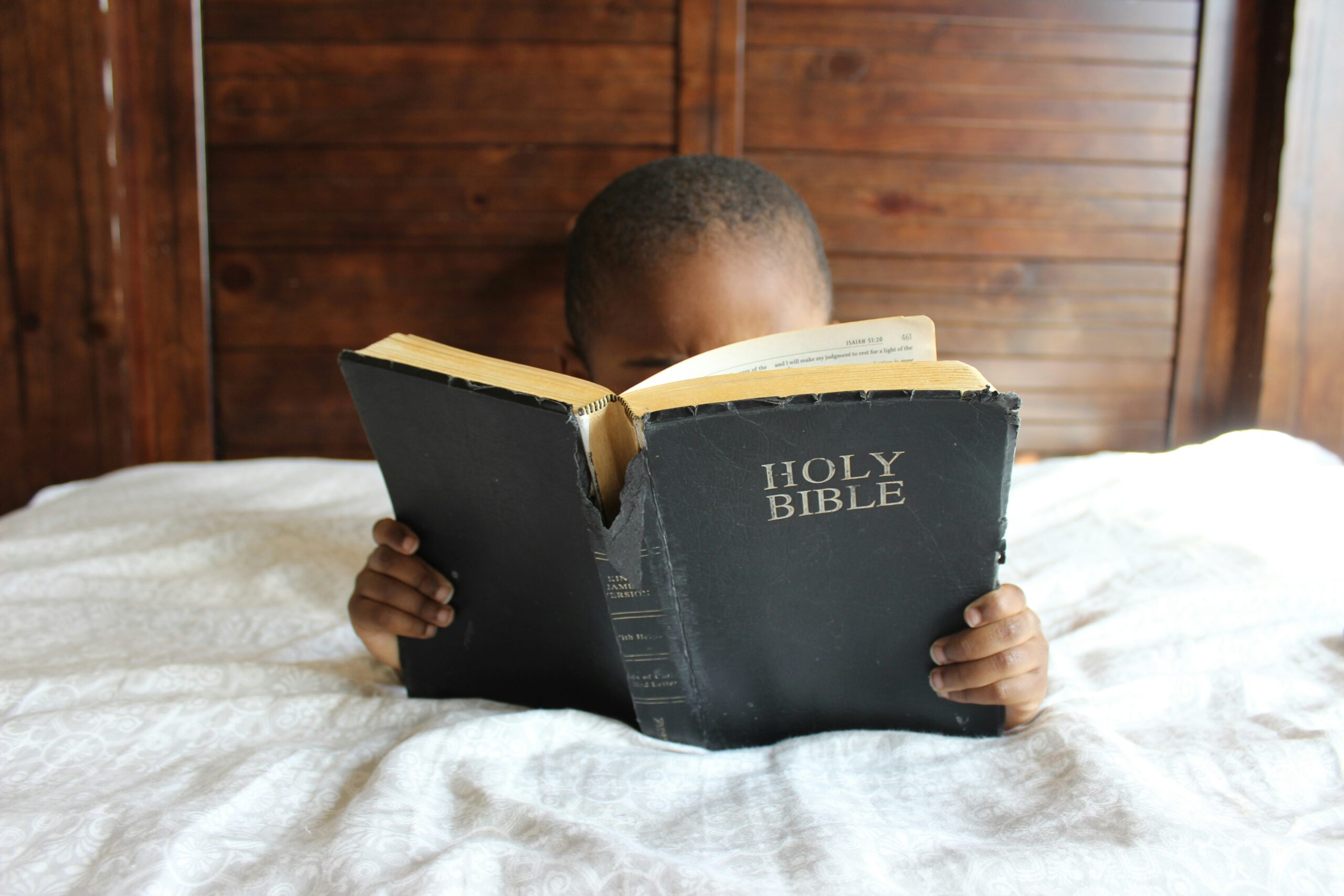

Biblical Foundations for Mutual Encouragement and Accountability

You see, scripture is filled with instruction for a different kind of disciple-making relationship. I’d go so far as to say that the vast majority of disciple-making happens in these kinds of relationships. The kind where experiences are shared, access is granted to one-another, and where there is mutual admiration. These are relationships where our primary role towards one another is friend. And, once you learn to look for those instructions, you begin seeing them everywhere. In Romans 15:14 Paul says “I myself am convinced, my brothers and sisters, that you yourselves are full of goodness, filled with knowledge and competent to instruct one another.” Then, in Colossians 3:16 he writes “Let the message of Christ dwell among you richly as you teach and admonish one another with all wisdom…”

I could go on. But, do you see it? There is an expectation that the work of moving one another towards becoming more and more like Jesus isn’t something reserved for the asymmetrical teacher-student, pastor-parishoner, leader-follower kind of relationships. Instead, it was meant to be the very content of friendship.

Why “Iron Sharpens Iron” Requires Relational Equity

Back to my good friend Greg.

Over the past 5 years, I can confidently say that I have become more like Jesus because of our friendship. I have learned how to be more generous with my time and money because I’ve seen him demonstrate it in ways that were foreign to me. I have learned to pray for my kids and simply expect that God will do something about it, because I’ve seen how God has done it in his life. I have learned about making good deals that also honor God because I’ve witnessed Greg genuinely serving people through his business. And, the crazy thing about this is that Greg would never admit that he has had any role in my discipleship! He is surprised when I bring it up.

My favorite thing about our friendship is that we could not be more different. I’m the outgoing type who talks too much. Greg is more reserved and would pay good money not to have to talk. I’m the “figure it out as we go” type, while Greg likes to think things through and is great with details and numbers. But the two of us are trying to become more like Jesus, and hopefully become better dads, husbands, and friends in the process. So, like “iron sharpens iron”, we have just enough friction to help each other grow.

Allow me to share a funny story. I invited Greg to come with me to Brazil last year. I was invited to speak at a missions conference, and would later preach at a friend’s church. The pastor at the church I was preaching at didn’t know much about Greg, and really didn’t have time to ask. So, I watched as the pastor, after my sermon, looked straight at Greg from the stage (this was a very modern church), and with a uniquely Brazilian accent he said in English: “Pastor Greg, come pray for us!” I could see his face grow pale, wanting to run away but also realizing there was no way out. He gathered himself, made his way up on stage, and prayed for those who were receiving Christ for the first time. So now, though we are friends, he holds authority over me as pastor Greg.

Here’s the point I’d like you to leave with: When it comes to healthy disciple-making relationships, parity and equity in friendship almost always carries more potential for mutual transformation than authority and asymmetry. So, seek out friendships where you will be the teacher and the student at the same time.

This is the final installment in a series dedicated to exploring what I have come to understand as the five foundations of disciple-making. I hope this is helpful to all of those who, like me, are laboring to help the Church become better at participating in the Great Commission. Join us in this conversation by downloading WME’s WE419 app, where you can engage with resources, post your thoughts, etc.

Subscribe

Get articles about mission, evangelism, leadership, discipleship and prayer delivered directly to your inbox – for free