There is a reckoning unfolding that we would avoid if we could – unless we are one of the people who have been crying out for it, praying for it, watching the horizon for it.

But the people who pray for revival and the people who pray for reckoning aren’t always the same.

In the open air of summer camp meeting, I watched with child’s eyes as adults around me responded to altar calls from evangelists. Most of the people sitting on rough wooden pews were not atheists; they were looking for sanctification. Often, they were looking for release – catharsis, tears, freedom in individual hearts and minds. Preachers cautioned against returning home without living out the work claimed to have been done in the heart kneeling at the altar rail. I lost count of the times I went to the altar to pray.

Good was done in those camp meetings. When revivalistic Protestants speak of revival, it almost always entails looking back and looking forward – back to something that was, forward hoping to see it again. A lot has been written in the past few years that helps to puncture the yearning for a supposed golden time or the vague chase for nebulous revival.

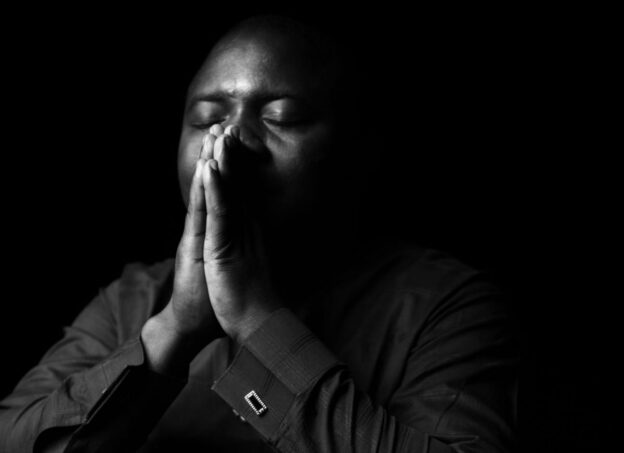

Exploration of travailing prayer looks at the presence of focused, laboring intercession preceding spiritual awakening within the footprints of church history. Travailing is childbirth language; it is the language of being in labor, experiencing the pain of contractions. Rather than lament the absence of an idealized past with varying descriptions of revival – rather than hope wistfully to experience those descriptions of revival if God chooses to allow it (as if God is preoccupied on the phone rather than willingly pouring out the power and presence of the Holy Spirit) – discussions of travailing prayer highlight the rhythms of awakenings around the world the past few hundred years. Through this, we find helpful posture and practices for those hungry for spiritual awakening. A willingness to engage in travailing prayer should precede scanning the horizon for signs of revival.

Discussions on travailing prayer seem to be a necessary and pivotal counterpoint to any approach to revival that reduces awakening primarily to a personal experience of subjective emotional response. If we do not accept the burden of laboring in travailing prayer, we cannot complain of the need for awakened revival.

But I would say today, on a cool spring morning in the early years of the 21st century, living and breathing on American soil, that the people who pray for revival and the people who pray for reckoning aren’t always the same people. But they may be praying for the same thing.

People who pray for revival may want Holy Spirit power; people who pray for reckoning want the power of God to flip the power of oppressors upside-down.

People who pray for reckoning are people who are already used to praying travailing prayer, because they don’t have to go far to find themselves groaning in spirit.

The power of God may be poised, waiting to see whether the people accustomed to praying for revival will awaken to the deep-seated memory that revival and reckoning were never separated in the first place.

Reckoning came before the glory of the Lord would be revealed. The apocalypse – the uncovering – the unveiling – the revealing of God’s glory – would not occur without reckoning.

The people of Israel learned and forgot this time and again.

When the Word Became Flesh and walked around revealing God’s glory to untouchables and undesirables and overlookeds and underfeds, reckoning thundered in his wake; the same God spoke the Truth of God and to some it sounded like blessing and beatitude and to others it echoed of woe and dread.

To desire God’s glory without submitting to God’s reckoning is to desire the benefits of God without the costs of the way of Jesus.

Judas wanted to be near power and glory. Judas was near power and glory. Judas could not submit to the reckoning that occurs in the presence of God who was walking around eating fish and raising the dead and sitting in the houses of imperial collaborators.

Judas acted out of self-preservation and then regretted it; but the apocalypse – the uncovering – the unveiling of his own heart and motives became a further moment of reckoning for the rest of the disciples. In the face of the crucifixion, they also faced the revelation of Judas’ actions. Gospel readers know that before Judas tried to bolt as a disciple, he embezzled from the treasury box – a box funded by wealthy women supporting Jesus’ ministry.

In Acts 1, about 120 men and women – disciples of Jesus – gathered together earnestly praying, before Pentecost – before the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. In the midst of this travailing prayer, before Pentecost, they face what Judas has done – “he was one of our number and shared in our ministry.”

Reckoning comes before revival.

Had the wealthy women disciples noticed discrepancies in the treasury and prayed for God to reveal the truth of what was happening?

Had Judas stolen from someone who’d given their last two mites, their five loaves and two fish? Had someone powerless seen his quick, hidden dip into the group funds? Had someone prayed for reckoning? Someone who was dismayed but not shocked to learn about Judas betraying Jesus?

We cannot pray for revival without being willing to face the reckoning. If we submit to the reckoning, we may or may not see revival, but we will have submitted ourselves to the justice, mercy, and power of God – “But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.” (Amos 5:24)

An impoverished unmarried woman prophesied in a time when her homeland was occupied by foreign forces:

“And Mary said:

‘My soul glorifies the Lord

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has been mindful

of the humble state of his servant.

From now on all generations will call me blessed,

for the Mighty One has done great things for me—

holy is his name.

His mercy extends to those who fear him,

from generation to generation.

He has performed mighty deeds with his arm;

he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts.

He has brought down rulers from their thrones

but has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty.

He has helped his servant Israel,

remembering to be merciful

to Abraham and his descendants forever,

just as he promised our ancestors.'”

This ferocity from the mother of Christ celebrates the fact that for many, reckoning means hope.

“He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things but has sent the rich away empty.” She rejoices because God has been “mindful of the humble state of his servant.”

Her suffering had not been overlooked; her humiliation had not been forgotten or ignored; the injustice experienced by her people was being answered in the arrival of the revelation of the Son of God – the God of jubilee and freedom, hope for widows and welcome for strangers.

People who pray for reckoning are people who are already used to praying travailing prayer, because they don’t have to go far to find themselves groaning in spirit.

There is a reckoning unfolding that we would avoid if we could – unless we are one of the people who have been crying out for it, praying for it, watching the horizon for it.

But the people who pray for revival and the people who pray for reckoning aren’t always the same.

Where in the Book of Acts can I find the Holy Spirit pouring out on groups of believers easily characterized by shared race – when that race is so predominantly represented because congregations and traditions sprang up geographically in places that less than a lifetime ago had Sundown signs posted at city limits? How can I say I long for individual and corporate spiritual awakening if I pray for revival in a room dominated by other white Americans?

Predominantly white towns and regions did not happen accidentally. Thousands of American churches are predominantly white because decades ago explicit signs or implicit laws made them that way and kept them that way.

Some of the oldest, storied, traditional Black Methodist denominations exist because white Methodists kept them out. Consider the AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Zion Church:

“The origins of this church can be traced to the John Street Methodist Church of New York City. Following acts of overt discrimination in New York (such as black parishioners being forced to leave worship), many black Christians left to form their own churches. The first church founded by the AME Zion Church was built in 1800 and was named Zion; one of the founders was William Hamilton, a prominent orator and abolitionist. These early black churches still belonged to the Methodist Episcopal Church denomination, although the congregations were independent. During the Great Awakening, the Methodists and Baptists had welcomed free blacks and slaves to their congregations and as preachers.”

Revival and reckoning had gone hand in hand – during the Great Awakening, Methodists and Baptists had welcomed “free Blacks and slaves to their congregations and as preachers.” But in the wake of the awakening, hearts closed; decades before the Civil War, the debate within the Methodist Episcopal Church over accepting Black ministers led to the official formation of the AME Zion Church.

Sitting in the humidity watching adults fumble down the aisle of the open air tabernacle toward the altar, crickets and cicadas loud against the singing of “I Surrender All,” almost every face around me was white.

How can God take seriously the prayers – even the travailing prayers – for revival and spiritual awakening that are prayed distracted from the cries, laments, and groans of those praying for reckoning?

We want revival only inasmuch as we desire to submit ourselves to reckoning, and the predominantly white Protestant Church in the United States on this Eve of Pentecost 2020 has shown nothing so clearly in the past six months as its damnable refusal to submit to anything, much less the convicting reckoning of Almighty God.

We want revival for ourselves and reckoning for our adversaries, rather than reckoning for ourselves and revival for our adversaries. The way of the cross of Jesus Christ welcomes the painful scrutiny of the Holy Spirit upon ourselves and the Holy Spirit’s merciful grace toward literally everyone else.

White Christians who pray for Holy Spirit power need to ask ourselves if we have a history of using power well. If we cannot answer that with a “yes” then we should beg God to spare us from pouring out any holy power on us that would consume us in its blaze. We should beg God to spare us until we have the character to withstand the presence of the Holy Spirit – “our God is a consuming fire.”

Desiring proximity to power and glory without submitting to the reckoning that occurs in the presence of God will place us squarely alongside a disciple – but not the disciple we would wish to emulate.

If revival does not come for you, it cannot come for me. If reckoning is what you are praying for, I cannot ignore it. If my prayers for revival sound trite while you groan for God to hear your pleas for justice, then I must join your groans and prayers for reckoning, sharing in your travailing as I can.

Ferocious Mary, mother of God prayed table-flipping prayers years before her son walked into the temple for a day of reckoning.

“He has performed mighty deeds with his arm; he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts. He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble. He has filled the hungry with good things but has sent the rich away empty.“

If Christians are baffled at why our prayers are being sent away empty, maybe we should consider that it is because we are avoiding the reckoning while praying for the revival. The arm of God will crash down on us like thunder if we think we deserve the outpouring of the Holy Spirit while avoiding truth; if we think we are entitled to revival while others need to prove their worthiness.

The Holy Spirit of God poured out on women and men, empowering them to speak in different languages. Jews from all different regions heard God calling out to them in their own languages, with their own words – God’s heart in the sound of their own accent:

“‘Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!”

Pentecost has always only meant that the pouring out of the Holy Spirit means hearing God’s wonders. The Holy Spirit was set loose witnessing to the Resurrected Christ: “He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.“

If I do not have ears to hear the groaning for reckoning, I do not have ears to hear the wonders of God.

If we justify church leaders who abuse their positions to exploit others, we do not have ears to hear the wonders of God.

If we ignore the groans of suffering people inside or outside the church, we have stopped up our ears to ignore the wonders of God.

If we resist the opportunity to learn our own history and the history of others so that we can better grieve and lament our broken, shared story, then we dim the volume of the wonders of God.

If we scorn the accounts of the hurting out of the compulsion to justify people who remind us of us, we silence the mouth of Jesus; we drown out the wonders of God.

A few months ago, Rev. Shalom Liddick preached on intercession. Anointed by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, she testified to this truth:

“I’m your keeper – you are mine. The fact that God came to Cain and asked, ‘where is your brother?’ tells me something. It tells me God will ask me about my community. ‘Hey – where is…?’ It is my responsibility to pray for you. Where are you, friend? We live in a culture where we want to be independent. But I need to make it a point to always present you before God, and you need to make it a point to present me before God.

Remember: you are your brother’s keeper; you are your sister’s keeper. You’re a watchman. And where God has placed you, God has placed you on purpose. Watchmen stand in the middle to communicate, to see, to defend. An intercessor stands in the middle to intervene on behalf of somebody else.

God calls me and calls you to be people who get in the middle and say, ‘God, can you help my sister? Can you help my brother? Can you help my community?’ God is present – in the middle – of everything.”

Reckoning comes before revival, and before we open our eyes on Pentecost Sunday, we must face the question of whether or not we have failed to be each others’ keepers. Whether we have neglected to stand in the middle and intervene.

In John Donne’s classic poem, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” he considers the question not only of inquiring whose funeral a bell announces, but also the dilemma of whose responsibility it is to ring a bell announcing a sermon. Reflecting on funeral bells tolling, he wonders if the bell could ring for himself, if he were too ill to realize how ill he was:

“PERCHANCE he for whom this bell tolls may be so ill, as that he

knows not it tolls for him; and perchance I may think myself so

much better than I am, as that they who are about me, and see my

state, may have caused it to toll for me, and I know not that.

The church is Catholic, universal, so are all her actions; all that she

does belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action

concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that body which

is my head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member.

And when she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is

of one author, and is one volume.”

Can one be so sick they do not recognize the extent of their illness – to such a degree that they do not realize the funeral bell tolls for them? Can our souls carry unseen disease, visible to those around us but hidden from ourselves, so that we do not even realize the reckoning is ours?

On responsibility to ring the sermon bell, he muses that those who realize the dignity of the task will quickly respond to share the responsibility: “The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth.” The bell tolls for the person who thinks it summons them.

But whether or not we have trained our ears to hear the summons is another matter. And this is the tragedy of Pentecost: “Some, however, made fun of them and said, ‘They have had too much wine.'” We cannot hear what we do not listen for. We cannot hear revival if we believe it doesn’t sound like reckoning.

Every time a funeral bell tolls for someone else, it tolls for me, because their death diminishes me.

“I’m your keeper. You are mine. God came to Cain and asked, “where is your brother?”

The people who pray for revival and the people who pray for reckoning aren’t always the same people. But they may be praying for the same thing.

Come, Holy Spirit.

And let justice, like revival, roll down.