Over a shop on the little island of Gozo in the Mediterranean where we often go on holiday is a faded yellow sign which is a monument to one of the biggest and most unexpected bankruptcies in recent corporate history. It reads KODAK. Kodak, remember them? Up until the end of the last century most of us would have owned a Kodak camera at some time in our lives and probably, whatever camera we had ,the likelihood is that it would have Kodak film inside and would be printed onto Kodak photographic paper. Kodak was a corporate giant that dominated its industry. Now just about all that remains are faded signs in out of the way places. So what went wrong?

Futurist Dr. Bob Goldman describes the demise of Kodak like this ….

In 1998, Kodak had 170,000 employees and sold 85% of all photo paper worldwide. Within just a few years, their business model disappeared and they went bankrupt. What happened to Kodak will happen in a lot of industries in the next 10 years – and most people don’t see it coming. Did you think in 1998 that three years later you would never take pictures on paper film again? Yet digital cameras were invented in 1975. The first ones only had 10,000 pixels, but followed Moore’s law. So as with all exponential technologies, it was a disappointment for a long time, before it became way superior and got mainstream in only a few short years.

The demise of Kodak, when you think about it, happened because its leadership kept carrying out its mission in the ways that had been successful in the past and realized too late that digital photography was going to take over the market and their film and photographic paper was appealing to an ever-shrinking section of the population, those really serious photographers who wanted the look it created and those older people who didn’t want the newfangled digital stuff and would stick to the their box brownie.

I remember at least 10 years ago Alan Hirsch passionately warning church leaders, as he still does, that they were making the same mistake as the directors of Kodak. What I mean by that is they were persevering with a form of mission which, whilst it had been successful in the past, was destined to appeal to an ever-shrinking section of the population. Here’s how I think the Kodak catastrophe is being played out in the church in the West right now.

Basically, the church in “Christendom mode,” the church that had operated in a culture which had some sort of Christian “home field advantage” carried out its mission predominately by reaching out to the so-called “fringe” around the congregation. As a newly minted pastor in the 1990s I followed my training and the advice I got from church growth books of the time and made my prime focus in mission those who came for my church for “hatches, matches and dispatches” – people who approached us for religious “services” and so were at least open to coming to church.

Around the turn of the century I attended a Purpose Driven Church conference in sunny California and was urged by Rick Warren to focus my efforts in evangelism on moving people from the crowd (the fringe) into the congregation. That strategy worked in the U.S. and to an extent in the UK; the problem is that its success was like the corporate success in 1998 for the Kodak corporation: it hid the upcoming technological tsunami that would all but wipe out Kodak’s business model.

If you Google (who uses Yellow Pages these days? It was another company that didn’t see the technology tsunami coming) “civil celebrants” you’ll see numerous people offering to do secular versions of “hatches, matches and dispatches.” Ask any undertaker and they will tell you that the number of humanistic funerals are surpassing the number of religious funerals. This year in Scotland more people have been married in places as diverse as hotels and on the top of mountains than church buildings. As for “christenings,” for those who aren’t church members they are now rarer than a Scotland appearance in international football competition.

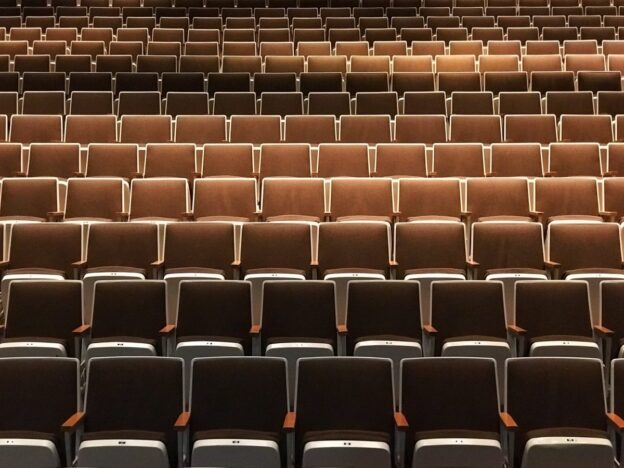

The problem as I see it is that in the face of this cultural tsunami, which is often described as “post-Christendom,” most church leaders are still acting like the directors of Kodak at the end of the 20th century. Fundamentally most established churches I know of are still committed to mission in the way that has been successful in the past, attracting the fringe of the church to attend events in the church building. The church now, like Kodak should have done over a decade ago, needs to face up to the fact we live in a changed and changing world. The stark truth is that the number of people seeking religious services from the church is becoming on a par with those who still prefer to use film and photographic paper rather than digital cameras on smart phones, that is, shrinking and probably soon all but gone.

The implications of this is that in the UK there are too many churches fishing in the shrinking pond of people who are still open to be attracted to church for that form of mission to be effective. The result is that congregations are having to become more and more competitive in attracting the diminishing number of people who are open to being attracted to church. I suspect this is why were are seeing growing numbers of “larger churches” if not megachurches in cities in the UK. It may also explain the success of the so called “megachurch franchises” like Hillsong and Saddleback which have sprung up and grown rapidly in London and other major European cities in the last decade. With the high profile, huge resources and training of their parent congregations these “franchises” can put on a better show than local smaller congregations and so are more successful at attracting those open to coming along to church. It seems to me evangelical churches in the UK are becoming increasingly like the fishermen of the North Sea: we are overfishing a diminishing stock, not of haddock, but of church fringe people, and the foreign megachurches and their clones are like the huge foreign factory trawlers; they fish more effectively and so will ultimately diminish the stock more quickly.

I had a conversation with the representative of a UK mission organization recently and he talked about how they were helping churches be more missional. When I questioned him further it was pretty clear what he meant by that was helping churches attract more people to their fringe who would eventually start attending church and hopefully eventually come to faith. To him “missional” meant being more committed to evangelism, being better at attracting unchurched people to church events, and of course we have just described the problem with that.

I doubt there is a more used and less understood word in the contemporary church than “missional.” Missional is not about being better at being Kodak in a digital photograph world. I don’t think anyone has done more to help the church understand what “being missional” is all about and is currently more frustrated by how the word is being used than Mike Frost. He writes in his book The Road to Missional:

My call and the call of many other missional thinkers and practitioners was not for a new way of doing church or a new technique for church growth. I thought I was calling the church to a revolution, to a whole new way of thinking and seeing and being followers of Jesus today. I now find myself in a place where I fear those robust and excited calls for a radical transformation of our ecclesiology have largely fallen on deaf ears. (p 16)

Mike Frost hits the nail bang on the head. Missional is not about new ways of doing church, better techniques for attracting those open to coming to church to actually walk through the church doors – it’s about a fundamentally different way of being church in a culture. I was walking around Motherwell recently, a bit of a down-in-the-heels Scottish town, when I saw a church building boarded up and decaying.

It reminded me of that Kodak sign in Gozo.

My prayer is that the current generation of church leaders would avoid the mistakes of the Kodak directors. That they would recognize that commitment to past successful methods in evangelism may be the biggest danger to effective contemporary mission and instead explore with the Spirit’s guidance what it means to be God’s people shaped by God’s mission in our world today.