Note from the Editor: The sudden news of Dr. William Abraham’s death sent Methodists around the globe reeling. Immediately, a flood a tributes began to pour forth in a kind of spontaneous online wake. Before Covid, wakes were still common in Ireland and also in Northern Ireland, Billy Abraham’s childhood home. In the remembrances that follow, four unique voices give tribute to the well-known scholar, preacher, and writer, joining the friends and colleagues gathering digitally who have instinctively touched on the loudest parts of traditional wakes – raucous laughter, robbed lament.

That is one theme that threads through stories, memories, hilarity, and loss the sense of being robbed. Robbed of the opportunity to say goodbye; robbed of the opportunity to clear the air; robbed of the opportunity to say thank you. Robust affirmation of the resurrection of the dead does not lessen the shock of sudden loss, does not blunt that very human sense that something dear was stolen.

Like C.S. Lewis, Billy Abraham was a son of Northern Ireland who went on to study at Oxford. The same year that Billy “was selected to matriculate into Portora Royal School in his hometown,” 1955, Basil Mitchell succeeded C.S. Lewis as President of the Oxford Socratic Club. Around twenty years later, Billy began his doctoral work on philosophical theology at Oxford under the direction of Basil Mitchell. And if anything characterized the primary currents in which Abraham’s thinking sailed, it was the imperative that drove that famously lively club – to “follow the argument wherever it leads.” This intellectual habit requires confidence in truth and reason, yet it also requires discipline to pursue unflinchingly. If anything else characterized the strongest currents of Abraham’s intellectual navigation, it was the ability to engage in – and enjoy – rowdy debate with collegiality.

Lewis knew the importance of these disciplines in general and for people of faith in particular, famously commenting, “In any fairly large and talkative community such as a university there is always the danger that those who think alike should gravitate together into coteries where they will henceforth encounter opposition only in the emasculated form rumour that the outsiders say thus and thus. The absent are easily refuted, complacent dogmatism thrives, and differences of opinion are embittered by group hostility. Each group hears not the best, but the worst, that the other groups can say. In the Socratic all this was changed. Here a man could get the case for Christianity without all the paraphernalia of pietism and the case against it without the irrelevant sansculottisme of our common anti-God weeklies. At the very least we helped to civilize one another.”

It is difficult to conceive of a more timely commentary for those who live in the United States, and it is worth noting that Lewis made this observation on the nature of community and coterie long before social media or the internet could easily be blamed. The Christian who argues with civility should not be an endangered species. And disagreement isn’t inherently uncivil.

Where Americans sometimes found themselves surprised by Abraham was often in this very sphere. Those who knew him to be orthodox were sometimes surprised by his intellectual freedom – caught off-guard when his quickly lilting accent slipped in a reference to the Holy Spirit as “she,” and perhaps unaware of the ancient tradition he was following. Those who knew him to prize the message of holiness were sometimes surprised when they expected a teetotaler and found a bottle of red wine. Those who knew of his theology – not only anthropology but also epistemology – were surprised when they expected hostility and were met with a friendly offer to get dinner.

There is rich freedom in intellectual honesty – in following the argument wherever it leads; and there is rewarding freedom in the ability to engage in rowdy debate with good-natured collegiality that isn’t precious with its participation. Any who are tempted to mine Abraham for the convenience or prestige of his doctrinal alignment without subjecting themselves to those same rigorous intellectual habits will find it puzzling as to why the relative scope of influence varies considerably. He did not require the soothing, damning chorus of an echo chamber, nor did he buckle to the fear that practicing common decency would be perceived as liberal drift.

If the Church in North America needs the movement of the Holy Spirit, it also needs the fruits of the Spirit as they are lived out in the intellectual life: love of the truth, joy in studying it and in the existence of friends and opponents alike, peace that reason well-employed is a gift from God, patience in crafting thoughts carefully and in giving others space to change their minds, kindness toward those who don’t fight fair or who have been mocked by your side, goodness in loving the ethical working out of belief, faithfulness to Christ over base red meat or crowd, gentleness with whomever has less advantage than you do, and self-control in speech, in loves, in choices, and in action.

When those grieving his loss feel robbed, it is in part because he influenced so many scholars, members of the clergy, and laity (he was a steadfast Sunday school teacher, not the least of his contributions to the Church) on a very personal level at vulnerable points in their professional or spiritual lives. But those grieving his loss feel robbed in part because in some way, from some angle, he showed us how to be better. Better thinkers, better colleagues, better friends, better opponents, better Christians.

As I told a friend, “he made me want to be better without ever making me feel small.”

My friend Maxie Dunnam, Founding Editor of Wesleyan Accent, is mourning the loss of his close friend. In the following, we share reflections on the contributions and character of Billy Abraham from a member of the clergy and from academics; from those who generally shared his perspectives, and importantly from one mourning his loss who sometimes disagreed with him profoundly. It would be a disservice to the scope of his influence to overlook those friendships characterized by mutual respect and genuine affection that also stood in the difficult tension of that old phrase, “the loyal opposition.”

In raucous laughter and robbed lament, we honor our feisty departed friend.

Elizabeth Glass Turner, Managing Editor

Dr. Joy Moore, VP for Academic Affairs & Academic Dean; Professor of Biblical Preaching, Luther Seminary

I am grateful to join the chorus of witnesses sharing individual expressions of how our lives were among the many influenced by one. I am embarrassed to say my first recognition of “exactly” who William Abraham was came years after I had publicly stolen a story from him. (No, this is not a preacher’s prerogative; and in all honesty, I had no idea the source of the illustration was sitting in the audience as I used his metaphor to underscore my point!)

When I finally did connect the dots, it provided an underscore to the kind of person Billy was: he never mentioned my faux pas. Instead, Billy shared his wisdom and perspective, providing me guidance as I made personal and professional decisions that would shape how I served the church and the academy. I will forever be grateful this author became a real person and friend in my life! Billy once introduced me before I spoke at a gathering with an honest evaluation of my style and substance that conveyed his knowledge of me was more than a superficial greeting at conferences or reading of my resume (yes, I shamelessly acknowledge that, because who wouldn’t want to say Billy Abraham introduced them publicly?).

I met Billy shortly after I began my doctoral work. His engagement with my then-incipient ideas provided soil that nurtured those seedling thoughts. Over the years of many stimulating conversations, Billy’s challenge, conviction, confession, and collegiality bore witness to truth-telling, tenacity, testimony, and tenderness that, for me, embodied a Wesleyan witness. As enchanting it was to hear theology expressed with an Irish twang (he did land in Texas), Billy captivated our imaginations with a confessional-critical interrogation of institutional and individual claims to a Wesleyan Christian practice that calls for a biblical imagination, theological integrity, and personal piety that boldly proclaims the faith in the Triune God.

As we pause together to grieve our loss and celebrate the gift of Billy’s presence in our lives, may each of us be challenged to live our lives with the integrity we experienced with Billy: lifting others to find their place at the table; examining, interrogating, and calling out claims of what is truth; and pointing always and only to Jesus.

Dr. Jerry Walls, Professor of Philosophy; Scholar-in-Residence, Houston Baptist University

Billy Abraham was trained in analytic philosophy at Oxford. More recently, he was recognized as one of the senior spokesmen for “analytic theology,” a movement that applies the techniques of analytic philosophy to the discipline of theology. The aim of analytic theology is to promote rigor and clarity of argument in the discipline. This emphasis is apparent in a number of Billy’s books, but I will highlight two examples.

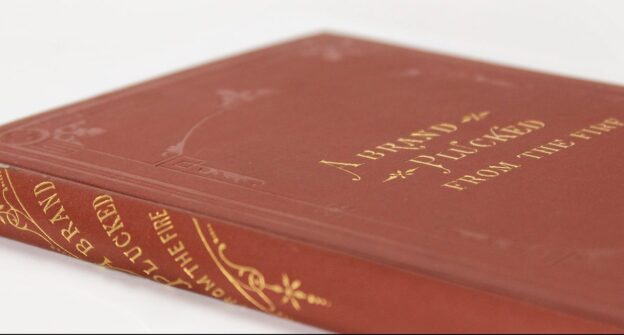

First is his volume from several years ago entitled Canon and Criterion in Christian Theology: From the Fathers to Feminism (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998). The very title of this hefty volume signals the important distinction that Billy wanted to clarify and defend, namely, a distinction between recognized canonical lists and epistemic criteria. A clear sense of this distinction is crucial to the argument, and Abraham lays it out for us at the very outset and reiterates it throughout his work. An ecclesial canon is essentially a means of grace, whereas an epistemic norm is essentially a criterion of rationality, justification, and knowledge.

To accent this distinction, Billy takes pains to remind us of the complex canonical heritage of the Church. For Protestants, the notion is associated almost exclusively with the canon of Scripture, but as Billy points out, there are several other kinds of canonical tradition deserving of recognition. These include baptismal and Eucharistic rites, liturgical traditions, iconographic traditions, lists of saints and teachers designated as fathers and mothers of the Church, and finally, the episcopacy as a means of supervision.

As Billy notes, however, there is considerable ambiguity surrounding the very meaning of canon. At one level, the word simply designates a list of books or other material. However, it can also signify some sort of standard which is used to measure and judge various doctrines, practices, and the like. This latter understanding of canon obviously has epistemic connotations and significance absent from the more modest notion of a list. Not surprisingly, Billy prefers the more modest notion and believes it better preserves the intended function of canonical material as means of grace which initiate us into the life of God and transform us morally and spiritually.

It is worth noting that the “Wesleyan quadrilateral” is an interesting instance of this very confusion between canonical lists and epistemic criteria. Whereas Scripture and tradition represent canonical lists, reason and experience are classic instances of epistemic norms.

The second example I will cite is his recently published four volume work entitled Divine Agency and Divine Action (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017-2021). Billy began working on this project over ten years ago, when he and I were both fellows in the Center for Philosophy of Religion at the University of Notre Dame. Billy and I shared an apartment that year, which was a delight in itself. Billy came to Notre Dame with a more modest plan, as he notes in the acknowledgments of the recently published fourth volume: “I had originally planned to write but one volume; within a month of my arrival at the university of Notre Dame it had sprouted into four.” Billy never hesitated to explore any relevant issues that arose in the course of his research, and it was a delight to watch him as he realized he had to put aside his original plan to write one volume and instead to produce four!

While philosophical issues frame the entire four-volume set, they are particularly emphasized in the first volume entitled “Exploring and Evaluating the Debate.” Billy notes there that much of the talk about divine action in contemporary theology is vague and elusive, hardly suited to do justice to the extraordinary claims of traditional Christianity. In contrast to all of this, he forthrightly defends a robust account of divine action that allows us to affirm unequivocally that Christ was born of a virgin, was raised from the dead, and will come again.

It is worth emphasizing that Billy wrote with grace, elegance, and winsome humor. Many of his books are accessible to thoughtful lay readers who could read them with great profit.

Rev. Dana Coker, Senior Pastor, First UMC Bonham, Bonham Texas

Billy Abraham is often misunderstood by people that don’t know him well. I also think he contributes to this misunderstanding. Part of the way he captured and kept our attention was by saying things in a creatively dramatic fashion. It was often hilarious if you happened to agree with him and anger inciting if you didn’t. I think, for Billy, it was worth it to make people mad because it frequently led to great debate and teaching opportunities. However, if this is the only side of Billy Abraham you knew (especially if you had lots of disagreements with him), well then, you just didn’t know Billy.

He was kind and attentive. Billy always looked me in the eye and was not only preceptive enough to notice if I seemed off, he would take the time to inquire and pray for me.

He was patient and generous. Many of the conversations that literally helped shape who I am, only happened because he was generous with his time. He made me feel welcome to come talk about whatever was on my mind in his office…or at his second office, La Madeleine.

He was a master at seeing potential and drawing it out. He believed in me before I did, and he seemed so happy to watch me find my theological footing.

His curiosity created an openness in him, but I only perceived his openness when he felt he was only among friends. After class one day, I told him he was wrong about something he said in class about a group of people, and miraculously I was briefly able to out debate the great debater. In amused frustration at his now grinning friend, he threw an eraser at me as I was walking out the door triumphantly. I few hours later, he poked his head into the room where I always studied and said, “You were right. I repent.”

In recent years, many things that he wrote and said publicly have been hurtful to me. Though Billy has said otherwise, there are people on both sides of the Methodist divide for whom scripture and the creeds are the backbone of their faith. He has too frequently compared the very best version of his side of the divide with the very worst version of the other side. Honesty escapes you, if you don’t see both misbehavior and great integrity and faithfulness on both sides.

I was upset with him. I was mulling over how I would start the conversation with him. I’m sure it would have been an extra lively debate. In fact, there might have been some tears, at least on my part, but I have no doubt it would have been a loving exchange.

Rest in peace, my friend! You have blessed my life and ministry, and I will forever be grateful!

Dr. Jackson Lashier, Associate Professor of Religion; Chair, Social Science Division, Southwestern College

The news of the recent death of William J. (Billy) Abraham affected me deeply. I have so appreciated reading many of the tributes to his life written by his former students and colleagues; he was certainly an extraordinary man. Unlike many of my friends in the Methodist world, I did not know Dr. Abraham personally, so my sense of loss is less personal though still profound. His impact on my life, as for numerous other professors, theologians, and pastors, came through his theological work.

I read Canon and Criterion in Christian Theology, his most well-known book, in a systematic theology class in my first year at seminary. At the time, I was a sola scriptura Protestant Christian who thought that church history skipped from the Apostle Paul to Martin Luther and that “canon” was a weapon used in early American wars. I used scripture as little more than a justification for my particular beliefs and figured the purpose of this theology class was simply to strengthen those justifications. I was, therefore, a little skeptical when first engaging this work, not least of all for its comprehensive argument and sheer length.

But Dr. Abraham’s winsome way, no less present in his writing than in his speech, gradually won a hearing and, perhaps providentially, Canon and Criterion toppled all of my assumptions coming into that class and more generally seminary. Through reading this book—under the skillful and patient guidance of my professor, Dr. Chuck Gutenson, himself a student of Dr. Abraham’s—I came to see how impoverished my understanding of scripture and the theological disciplines were. Scripture was not simply a justification of a set of beliefs, Dr. Abraham argues, but a “means of grace” given to us by God “to initiate us into the divine life” (53). What an infinitely more beautiful and compelling image of the Holy Scriptures!

Moreover, Dr. Abraham showed me that scripture was not the only means of grace so given by God, but rather, the canonical tradition of the Church included a whole host of means, including the sacraments, creeds, iconography, saints and church fathers and mothers, and the like. Not only is it appropriate to utilize these means as Protestants, it is necessary if we are to become the disciples God calls us to be. After I finished reading the book, I wanted to know what these other means of grace were and I wanted to read scripture like Billy Abraham did.

I’ve come to realize that Canon and Criterion shifted my whole perspective not just on the purpose of scripture and the other canonical materials but also on theological education. It opened me up to the formative practices of heart and mind on offer at seminary. It helped me to realize that I wasn’t in seminary simply to gain some more good arguments for my particular brand of Christianity or even to gain a better understanding of the scriptural foundations of my beliefs and practices. Rather, I was in seminary to be formed as a disciple of Christ, to be further initiated into the life of God. So too did my understanding of the role of a pastor change, from a person who makes arguments and reflections on scripture to a person who, using the canonical materials, helps initiate others into the life of God.

Finally, Dr. Abraham’s tantalizing introduction to these canonical materials, what he calls a “grand symphony…which leads ineluctably into the unfathomable, unspeakable mystery of the living God” (55), set me on a course of study that changed my vocation. It took me into a study of early Church history, the formation of the creeds, and the lives of the saints, a course of study I am pursuing to this day as a professor and writer. Now I want to teach and write like Billy Abraham, though I harbor few allusions that this is the case. From what I have read and continue to read of his, and from what I know from friends who took his classes, Dr. Abraham stood alone.

Precisely because the Church’s canonical tradition is a grand symphony of harmonious parts, Dr. Abraham suggests that it is never fully closed. Rather, he writes, “new canonical materials and practices can be developed to enrich the life of faith so long as they fit naturally and appropriately with the canonical tradition already in place” (55). If this is true, certainly Dr. Abraham’s person and work now passes into the grand symphony; his work has so clearly served as a means of grace in my own life and in the lives of countless others. Well done, good and faithful servant.