No one has seen more clearly than G. K. Chesterton that Christian theology is defined by a certain kind of benelovent paradox. The stretched arms of the cross extend infinitely in either direction, holding all goods together, even virtues that might seem to be opposed. Chesterton writes:

This was the achievement of this Christian paradox of the parallel passions…St. Francis, in praising all good, could be a more shouting optimist than Walt Whitman. St. Jerome, in denouncing all evil, could paint the world blacker than Schopenhauer. Both passions were free because both were kept in their place. The optimist could pour out all the praise he liked on the gay music of the march, the golden trumpets, and the purple banners going into battle. But he must not call the fight needless. The pessimist might draw as darkly as he chose the sickening marches or the sanguine wounds. But he must not call the fight hopeless. So it was with all the other moral problems, with pride, with protest, and with compassion. By defining its main doctrine, the Church not only kept seemingly inconsistent things side by side, but, what was more, allowed them to break out in a sort of artistic violence otherwise possible only to anarchists. Meekness grew more dramatic than madness. Historic Christianity rose into a high and strange coup de théatre of morality–things that are to virtue what the crimes of Nero are to vice (“The Paradoxes of Christianity,” Orthodoxy).

Chesterton’s point here is that, in Christ, the extremes of virtue are made possible as the angled mirrors of the lives of the saints blindingly reflect different aspects of the spectrum of the divine light. A terrifying fierceness is made possible in Christian soldiers, capable of overthowing armies far more powerful (e.g. St. George and the dragon, or St. Germanus facing the Saxons). And an even more terrifying compassion is made possible in Christian martyrs, meeting death as a welcome friend (e.g. Ignatius or Polycarp).

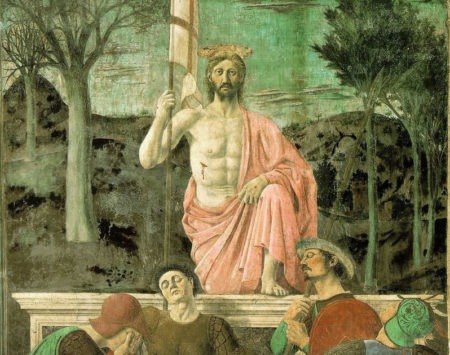

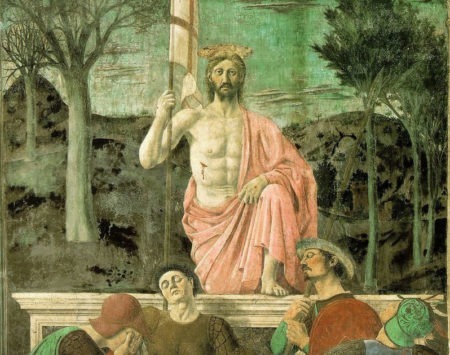

The same may be said of Christian art, which is at once angrily iconoclastic about false images of God, but also adoring of images that help us to see God’s nature.

The focal point of Christian thinking about the image is in the second council of Nicea, which faithfully follows the logic of the first council of Nicea by recognizing that if God has united Himself to humanity in Jesus Christ, there is no longer any reason why the human artist cannot picture God through Jesus Christ, and use the image to honor God.

St. John of Damascus, in his first treatise of On the Divine Images, says this well:

In former times God, who is without form or body, could never be depicted. But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter; I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake, who willed to take His abode in matter; who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I honor it, but not as God. How could God be born out of things which have no existence in themselves? God’s body is God because it is joined to His person by a union which shall never pass away. The divine nature remains the same; the flesh created in time is quickened by a reason endowed soul. Because of this I salute all remaining matter with reverence, because God has filled it with His grace and power. Through it my salvation has come to me. Was not the thrice-happy and thrice blessed wood of the Cross matter? What of the life bearing rock, the holy and life-giving tomb, the fountain of our resurrection, was it not matter? Is not the ink in the most holy Gospel-book matter? Is not the life-giving altar made of matter? From it we receive the bread of life! Are not gold and silver matter? From them we make crosses, patens, chalices! And over and above all these things, is not the Body and Blood of our Lord matter? Either do away with the honor and veneration these things deserve, or accept the tradition of the Church and the veneration of images.

John of Damascus grounds the making of image in the incarnation (the “taking on flesh”) of Jesus Christ, who “married” heaven and earth through the union of God and man. If the God-Man Jesus is the “express image” of God, as Hebrews 1:3 says, then the artist is free to express himself creatively, using the material of the world to faithfully image God in Christ.

Because of the expression of God’s image in Jesus, Christians are not bound to be simply “people of the book” (like Jews and Muslims) but can as truly be said to be “people of the image” (unlike Jews and Muslims).

For this reason, Nicea 2 not only allows image making, but forbids speaking against divine images which the invisible God has made visible.

Christian theology and practice are therefore boldly positive (or we might say, “courageously cataphatic”) about our ability to speak of and image God. Representative images of Jesus, Mary, angels, the saints, and the cross fill our churches, and we do not blush.

But the church’s artistic life has been traditionally wary of picturing what cannot be seen. Nicea 2 allows for a set of images that does not include the picturing of the Father, who is seen “through Jesus” (Jn. 14:9). In the early church, the practice of not picturing the Father was followed, and continues to be emphasized in the Eastern church. The Synod of Moscow in 1667 explicitly prohibits picturing the Father.

This negative prohibition (we might say, this “appropriate apophaticism”) is an attempt to maintain the paradox of Christian theology, that God is both immanent and transcendent: with us and also infinitely beyond us (Jn 1:18; Jn. 6:46; Ex. 33:20).

Christian artistic practice in the West has drifted from this apophatic dimension of theology. After the split between East and West, the Roman church began to picture the Father more and more. The most profound expression of this is seen on the ceiling of the Sistene Chapel, where the Father, resplendent in a white beard, creates the sun and moon and touches life into Adam.

Even this image, which many would say upsets the balance of Christian artistic worship, is not without grounding in the witness of scripture, which describes God as the “Ancient of Days” with clothing and hair “white as wool” (Dan. 7:9). But a more serious-minded artistic practice is governed by clearer scriptures, which teach us that the Father cannot be seen by us here and now (1 Tim. 6:15-16).

As is often the case, we cannot simply banish the bad without replacing it with the good. The best corrective for improper images is not no images, but rather faithful images.

One faithful artistic image comes from an unlikely source, a Jewish artist named Marc Chagall, who was fascinated by biblical imagery from the Old Testement and the New Testament. Some of Chagall’s most famous paintings picture Christ crucified, often juxtaposed with the suffering of the Jews in the 20th century. Jesus, the most famous suffering Jew, crucified at the hands of the Roman empire, represented the plight of Jews suffering during the Russian pogroms and German final solution. To emphasize his Jewishness, Jesus was often pictured wearing the prayer shawl of his beleagered kinsmen.

Chagall’s Jewish heritage helps to recover something that has been, at times, lost in Western religious art. In his paintings of Moses, he brings us back to a key theological moment in God’s self-revelation, which at once evokes the paradox of God’s radical transcendence and His desire to be known by us.

Chagall’s simple-but-beautiful images of Moses’ encounter with God at the burning bush interpret the apophaticism of God’s nature by showing God’s appearance, which is still shrouded in mystery.

In his numerous paintings of the encounter of the burning bush, God is only seen through the burning bush, or through an angel of the Lord. In a few versions of the painting, however, though the angel is present, God is seen through the burning bush and through the divine name, which emanates in the form of the Hebrew tetragrammaton (YHWH).

It is here that Chagall captures the paradox of the God’s self-revelation, which is at once personal (God’s name is revealed), but also veiled in mystery (he is only seen through the burning of the bush). Divine glory shines forth from the name, and extends to Moses, whose face shines, and is crowned with horns of light. (The horns are from the Latin Vulgate mistranslation of “shining.”)

Even God’s self-revelation of his name here is marked by the paradox of revelation. God’s name is “I AM,” a concrete set of syllables by which God can be specified. As Tom Oden writes, “Calling Yahweh by name is something quite different from speaking abstractly of an ‘unmoved mover’” (Classic Christianity, 57). Speaking of himself as “I” requires a conscious self. God is personal. Yet God’s name is mysterious, a self-description that defies easy understanding. God speaks of himself as “I am that I am” without a predicate attached. This self-referential way of speaking suggests a being that is being itself, as if his very existence is not defined by anything in this world at all.

To return to Chesterton, we may say that the virtues of God’s revelation stretch to both extremes:

God is both personal and beyond any categories we have for understanding personhood.

God is both present to us and utterly beyond us.

God is both known by us and unknowable in his innermost being.

God is both visible through Jesus and unseen as the Father.

This is the paradox Christian art has tried to maintain, often imperfectly: to proclaim God’s self-revelation in Christ and the hiddenness of God in his very being.