Today Wesleyan Accent is pleased to share this sermon drawn from 2 Timothy 1:1-7 from United Methodist pastor Dr. Kevin Murriel.

Today Wesleyan Accent is pleased to share this sermon drawn from 2 Timothy 1:1-7 from United Methodist pastor Dr. Kevin Murriel.

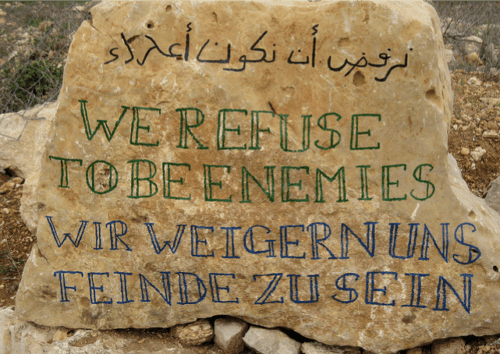

Today Wesleyan Accent offers timely wisdom from Rev. Michelle Manuel in her sermon, “Sticks and Stones,” on the freedom of loving our enemies. The sermon begins at the 27 minute mark.

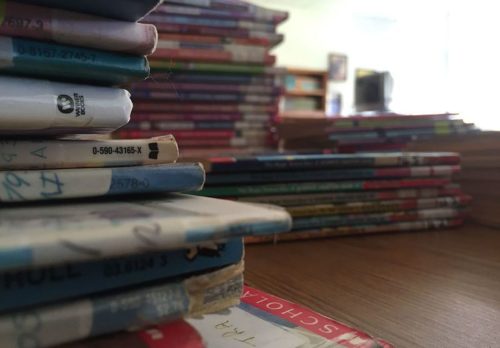

Note from the Editor: Following our series of posts exploring theology and literature –  from Steinbeck and the prophet Jeremiah to Jane Eyre, Jane Austen and John Wesley to the poetry of Mary Oliver – we asked several pastors and preachers from various Wesleyan/Methodist denominations what works of fiction have had the biggest impact on them personally.

from Steinbeck and the prophet Jeremiah to Jane Eyre, Jane Austen and John Wesley to the poetry of Mary Oliver – we asked several pastors and preachers from various Wesleyan/Methodist denominations what works of fiction have had the biggest impact on them personally.

Here are some responses:

Probably something from childhood: A Wrinkle in Time, especially Meg Murray, feeling awkward but finding herself and fighting for love. – Dr. Beth Felker Jones

Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God – Rev. Yvette Blair Lavallais

Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God – Rev. Yvette Blair Lavallais

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. I am now reading it to my boy. – Rev. Edgar Bazan

The Alchemist by Paulo Coelha, although there were a few books that I read as a kid that influenced me as well! Narnia series count? – Rev. Rob Lim

I think about Gilead by Marilynne Robinson a lot. – Rev. Jennifer Moxley

The Little Engine That Could – Rev. Kelcy G.L. Steele

Hinds Feet on High Places. That would be my number one. – Rev. Carolyn Moore

*What works of fiction would you include? Leave answers in the comments below.

Unless you live in Cleveland, tear up your notes and call the worship pastor: this Sunday, your sermon will practically write itself.

With phrases like, “‘Next year’ is finally today,” “the curse is broken,” and “‘someday’ is now,” your parishioners don’t have to be diehard baseball fans to appreciate the unbridled glee sweeping every corner of Chicago and most parts of the nation. With these words barely a step removed from the famous, “it’s Friday, but Sunday’s coming!” or the Narnian, “it’s always winter, never Christmas,” the time is ripe to remind congregations exactly what hope looks like in the Kingdom of God. Or gratitude. Or perseverance. Or faith. Or loyalty. Or fulfilled eschatological hope. Or goat-related curses.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b4LrTkWq9jU

So what do you do with all this frenzy when you’re not rewatching clips of Bill Murray’s existential ecstasy? Here are a few ideas for this Sunday:

If you didn’t hold an All Saint’s service last Sunday before the day, consider honoring the “great cloud of witnesses” this Sunday. What has been said in multiple interviews last night and this morning, by everyone from Bill Murray on the field to fans in Chicago pubs? “I’m thinking about my Mom, my Dad, my Aunt, my Uncles, if they could see this, I wish they could be here.” Cue grown men weeping. One Facebook acquaintance has been posting photos of her mother’s tombstone with a tally of Cubs postseason wins in the corner. Another acquaintance commented that his father lived his entire life, birth to death, without ever seeing a Cubs World Series win.

So it’s not bad timing to consider the Church Triumphant – “(Latin: Ecclesia triumphans), which consists of those who have the beatific vision and are in heaven.” It’s interesting that a baseball game could immediately evoke deep emotion about family relationships, grief, and loss, but it’s a dynamic not unlike the Israelites who wandered in the desert vs the Israelites who entered the Promised Land. It’s also not unlike some observations from an episode of Very British Problems on feelings and emotions, in which it was observed that a football (soccer) win allowed usually emotionally restrained men to weep, laugh, and hug publicly – a useful and socially acceptable catharsis.

Preach on what it means to fail spectacularly and publicly. In 2011, a documentary called Catching Hell came out about the nauseating incident when one well-meaning fan cost the Cubs a trip to the World Series. Steve Bartman had to be escorted out of the stadium by security after attempting to catch what he thought was a foul ball. It wasn’t. It was in play, and he kept the player from catching it. The fan’s name, place of work and even the subdivision he lived in were published in the paper the next day. He got death threats, scorned by an entire city. If there’s one person who would need an alias to have a Facebook profile, it’s this guy. Wikipedia has a page just called, “Steve Bartman Incident.” His name is synonymous now with being the guy who singlehandedly wrecks everyone’s hopes. If there was anyone praying more fervently last night than Bill Murray, it was this guy. Maybe he can sleep a little better – and safer – now. (Post-publication update on Steve Bartman’s response to the win here.)

How does this apply to a sermon? Well, redemption of inadvertent but spectacular failure is certainly a strong message. The story of Jonah might be powerful – one man’s presence due to disobedience threatening to sink a shipful of sailors. So also is the truth of what happens when a crowd turns nasty (plenty of examples of that in the book of Acts). Consider the classic hymn, too – “When I do the best I can, and my friends misunderstand, Thou who knowest all about me, stand by me.” *Note: this might best be preached by a pastor to a group of pastors.

Celebrate what it means for the Curse to be broken. According to Chicagoland lore, a local bar owner  bought tickets for himself and his goat in the 1940’s. After his intended good luck-goat was barred from the game, he pronounced a curse on the Cubs and they couldn’t manage to make it into the World Series ever after. Now, most North Americans don’t actually believe in curses, though many of us are casually superstitious about certain things. What built up though was a culture, an identity of being the “Lovable Losers.” The Cubs losing became something familiar, comfortable, but as food for the hope for tomorrow – “someday.” Someday, all the way. Next year. For the Chicago Cubs, it was always regular season, never World Series. It was Friday, but maybe, someday, Sunday would come. The fans kept coming, rain or shine, for the hope of tomorrow, because today stunk. Someday, though. Someday.

bought tickets for himself and his goat in the 1940’s. After his intended good luck-goat was barred from the game, he pronounced a curse on the Cubs and they couldn’t manage to make it into the World Series ever after. Now, most North Americans don’t actually believe in curses, though many of us are casually superstitious about certain things. What built up though was a culture, an identity of being the “Lovable Losers.” The Cubs losing became something familiar, comfortable, but as food for the hope for tomorrow – “someday.” Someday, all the way. Next year. For the Chicago Cubs, it was always regular season, never World Series. It was Friday, but maybe, someday, Sunday would come. The fans kept coming, rain or shine, for the hope of tomorrow, because today stunk. Someday, though. Someday.

In case you’re unclear what I’m driving at, let me connect the dots: Christians believe we don’t know how many extra innings we’ll go into, but we do believe that the Cosmic curse – our fall from Divine grace – has been lifted. The Book of Revelation gives a glimpse of the fireworks and victory laps to come: it gives a glimpse of the locker room celebration, even though we don’t know exactly who will get the runs or outs, or when. But in the Kingdom of God, Steve Bartman gets invited into the locker room for the afterparty.

In the midst of Narnia’s state as C.S. Lewis described it, where it was “always winter, never Christmas,” the residents of the fictional land still clung to a prophecy:

Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teach, winter meets its death

And when he shakes his name, we shall have spring again.

After all, we read in Revelation 22,

No longer will there be any curse. The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in the city, and his servants will serve him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. There will be no more night. They will not need the light of a lamp or the light of the sun, for the Lord God will give them light. And they will reign for ever and ever.

The Curse is broken, indeed.

Enjoy this piece from our archives following this week’s reflections on Steinbeck, Austen, and Bronte. For more literary reflections, enjoy this post from our archives on reading, preaching, and T.S. Eliot.

“Read everything.”

Rev. Steve DeNeff, a pastor and well-known preacher and speaker in The Wesleyan Church, said this one day in my undergraduate homiletics class. He is an excellent communicator and taught a fascinating preaching class. At the end of the second semester, he presented students with a print portraying a pastor in a pulpit, surrounded by shadowy figures – prophets and leaders from familiar biblical texts. “Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses…” it reads. It is an encouragement: you never step into the pulpit alone. Preachers are part of a fellowship of truth-speakers that stretches back across centuries.

“Read everything.” News stories, fiction and nonfiction books, magazines. It was practical advice – we had to assemble folders of cut-outs or printed pieces from the web or photocopied pages of books, a built archive of potential sermon illustrations that might work well as an introduction to a text or an illumination of a difficult principle.

“Read everything.” The advice was also given almost like a pronouncement, a warning, an exhortation: if you preach, you must know the culture in which you live and breathe. A lot of our cultural dynamics go unspoken – but if you read regularly, you will notice trends, changes, you will be aware of the atmosphere others breathe unconsciously.

Reading everything didn’t mean ignoring the scriptural text in a sermon: on the contrary, DeNeff made clear that a sermon that doesn’t reference the Bible after the initial reading isn’t a sermon, it’s a motivational speech. Rather, reading everything means voraciously pursuing every tool at your disposal to help communicate the Word of God.

So what happens when preachers read?

You gain perspective. If all you read is Tweets and football scores, your perspective will be limited. When you read the news (even skimming stories outside your usual areas of interest), you become aware of the big picture. If there’s any danger in church life, it’s becoming so wrapped up in your own denomination or geographical area that you forget to pop your head up and see what’s happening around you. Because most preachers also make hospital visits or review committee budgets or calm disputes or counsel troubled couples, it’s even easier to get so wrapped up in other areas that the habit of reading is seen as a luxury. If a preacher does read, it’s a book – often from their own denominational or traditional perspective – about leadership, ministry, or preaching.

You gain perspective. If all you read is Tweets and football scores, your perspective will be limited. When you read the news (even skimming stories outside your usual areas of interest), you become aware of the big picture. If there’s any danger in church life, it’s becoming so wrapped up in your own denomination or geographical area that you forget to pop your head up and see what’s happening around you. Because most preachers also make hospital visits or review committee budgets or calm disputes or counsel troubled couples, it’s even easier to get so wrapped up in other areas that the habit of reading is seen as a luxury. If a preacher does read, it’s a book – often from their own denominational or traditional perspective – about leadership, ministry, or preaching.

Which is about the moment that we begin to get nearsighted. But when you read – whether hardback or Kindle or even audio book – you deliberately expose yourself to other times, to other places, to other voices. Reading Dickens will throw into sharp relief how much things have changed in just a short 150 years – and how much they’ve stayed the same. In a time when all news is “BREAKING!” headline, it’s valuable to get some perspective. How far have we come? Where was God faithful in the Middle Ages? What circumstances from 50 years ago might give us some wisdom as we face today?

You gain storytelling awareness. If you read or listen to fiction, you will inevitably become – at the least – a slightly better communicator. Writers read good writers. Reading a good writer makes you a better writer. Of course not all books are worth your time. Some of them are worth investing in, though. By reading “Moby Dick” or “Roots” or “The Violent Bear It Away” or “Americanah” or even “Harry Potter,” you allow yourself to be a listener – a good discipline for speakers in itself – and to be swept up in the tide of the story itself.

Dr. Sandra Richter tells her Old Testament studies students to “tell the Story, and tell it well.” The more shy you are, the more I encourage you to read really good stories. They will help give you the words to express yourself.

You gain a disciplined mind by engaging new texts. Pastors have a lot of spinning plates, to use a familiar image. You’re busy. You’re subjected to the need for ruthless time management. But consider this benefit of reading fiction, nonfiction, news articles or poetry: you are subjecting yourself to the discipline of engaging new texts.

And that’s what you ask people to do every week.

Biblical literacy is at an astonishing low in North America: people who grew up in the pews are often unfamiliar with Bible stories and biblical themes. When you add people who did not grow up in the pews, even if you hand them a Gospel + Psalms, you are asking them to engage in reading that might, for them, be a challenge. Even listening to the Bible on your morning commute can be a challenge if you’ve never read it before.

Many pastors delegate Bible study to small group ministries. While whether actual Bible study actually happens in the fruit salad and coffee context of living room discussion is up for debate, it is the preacher’s job to proclaim the Word of God on Sunday mornings. And when you’re asking people to engage with the Word of God throughout the week, whether individually or in groups or through whatever book they’ve picked up at their local Christian book peddler’s, you should be willing to discipline yourself to read texts that are, for you, out of your comfort zone.

Reading one chapter of Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time” will probably remind you of how it can feel to encounter the  Bible as a newcomer to the faith.

Bible as a newcomer to the faith.

You gain sermons that grow beyond the surface. Truth pops up across history in many ways. There’s extraordinary wisdom about

human nature in Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice.” You can dog-ear pages of “Watership Down” or even smile at “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.” If I preach to a certain demographic of college students, I can communicate difficult Christological truths in a cultural shorthand with just one or two short quotes from “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince.”

Many people need to move from the familiar to the alien, from concrete to abstract. Jesus knew this in his own preaching. To prophetically proclaim is to take people on a journey. When pastors read, pastors deliberately invest in looking for effective ways to communicate the truth of scripture. Engaging in classics not only allows you to use stories and images that will engage your listeners as you bridge them to the biblical text, but also allows you to engage listeners whose intellects will appreciate the connections you draw – say, between Naaman’s vulnerability to his soldiers as he bathed in the river, and the struggle for dominant tribal position illustrated in a jungle animal fight early in Kipling’s “The Jungle Book.”

You gain health. Preachers, you are as hungry after mental work as you are after physical work. Only you haven’t expended near as many calories. Which means you’re ravenous after you write or preach your sermon, even if you haven’t been chopping firewood or playing basketball. In other words – you may be sedentary and very hungry, a potentially problematic combination. That’s on top of having a job that elevates blood pressure and steals hours of sleep.

But reading can boost your memory and reduce your stress; neuroscientists have discovered that reading a novel increases your brain connectivity; when you’re ready to clobber a difficult church member, reading can help increase empathy. (Just maybe read a paper version and not a screen that emits light right before bed.)

So when you have to fill out a report on your wellness practices, you can include “reading” on the list.

Last week I encouraged everyone to take a nap.

But if you’re in a preaching rut or having trouble sleeping, I recommend a good book.

Each Sunday before I enter worship, Ms. Ruth holds my hands and prays for me. Ms. Ruth, or “Mama Ruth” as I affectionately call her, is a senior member of our church who happens to be a white woman. She grew up in the Cliftondale community and has remained a faithful member throughout the over 50 year history of our church. Ms. Ruth not only attends worship but nearly every Bible study, mission and fellowship event that our church hosts. In other words, she is all in.

But she also sticks out. She is easily noticed in a church full of black worshippers. Yet, she is a part of this beloved community of believers seeking to live out the Great Commission of Jesus Christ.

In recent weeks, I have had conversations with many of my white colleagues about white privilege. The ethos of these conversations hinges on the inarguable fact that because of a person’s skin color, they are afforded more equity in our culture.

To be honest, these conversations have not yielded much hope for better days to come.

There seems to be a shift in how many view the acknowledgment of their white privilege. For many, this acknowledgment is important and it appears liberating—to finally admit that “I am white, and I have privileges black people do not.” So strong is this ideology among many white church leaders, those in theological circles, and some in society, that it rings loudly of “White Liberation!” suggesting that acknowledging ones’ privilege has liberated the individual from the bondage of systems that work on their behalf.

This is a fallacy.

The thought hit me recently as I witnessed the insensible comments of Mr. Trump as he finally recanted his role in the “Birther” controversy regarding the citizenship of our already two-term black president. My thought, like many, was, “I suppose President Obama’s citizenship is now validated since a white man who could possibly become our next Commander-in-Chief has said so.”

This type of unintelligible and nescient language is what keeps our country in the pit of racial injustice and division. It also gives more breath to white privilege.

If I may go out on a ledge and state what most black people think each time we hear a white person say, “I am privileged and I feel guilty about it;” please do not insult the intelligence of black people by telling us what we already know, feel, internalize, live in, struggle with, fight against, tolerate, mourn over, protest about, march and die for. As if black people should give a philanthropic or ethical achievement award to every white person who feels liberated by the acknowledgment of their privilege.

And the timing of these comments makes them seem inauthentic. If it takes black blood to spill on the streets and unarmed black and brown people to die for white people to admit they are privileged, there is something seriously wrong with such a liberating theology.

Black people do not only struggle against racial profiling and injustice, we are unequal economically, professionally and institutionally—all of which relate directly to white privilege.

When a white man, who is a major party nominee for president states unashamedly that our black president (eight years later) was born in the United States without fear of reprimand or loss of support, he is operating in white privilege.

In the potent work of liberation theologian James Cone titled, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, he suggests that:

In the “lynching era,” between 1880 to 1940, white Christians lynched nearly five thousand black men and women in a manner with obvious echoes of the Roman crucifixion of Jesus. Yet these “Christians” did not see the irony or contradiction in their actions.

I argue that not much has changed today. I am concerned with the white Christian who can worship Jesus and not spend time with or get to the know the culture of Christians who are black.

I am concerned with the white Christian who in the same breath can acknowledge their privilege and condemn someone for peacefully protesting racial injustice wearing a football uniform while the national anthem plays.

I am concerned with the white Christian who wants to do something prophetic like telling other white people in their churches that they are privileged while at the same time only communing with white people.

I am concerned with the white Christian who has never been the minority for an extended period of time in any setting.

These are but the genesis of my concerns.

Yet I am truly concerned with the white Christian who thinks they are liberated by knowing they are white and privileged (which makes that privilege more dangerous).

The Lord revealed something unique the last time Ms. Ruth prayed for me. God asked me, “have you noticed that she never apologizes for being white or the horrendous history she is associated with because of her skin color? Have you noticed that she never acknowledges openly that she is privileged? Do you see how she hugs you and all the other black folks with whom she worships? Do you hear how she greets you with the words, ‘my pastor?’ Are you noticing how she sits and eats with you and wants to know more about your likes and dislikes?”

In that moment I received this revelation: She is not seeking liberation, she is modeling reconciliation through genuine love.

To my white brothers and sisters, focus less on explaining your privilege and start being in community with black people. Perhaps that is the best path towards the prophetic.

One time as I came down from a platform during a church musical rehearsal, I passed several women and whispered, “I’ll be right back, I have got to go to the bathroom!” I rushed away and couldn’t hear the laughter that erupted behind me; the sound guy had not yet muted my lapel mic.

My whisper had been heard throughout the sanctuary.

When it was, Blessed Among Men turned off my microphone so that no further personal audio echoed through sacred space.

There’s been a lot of discussion in the public square about the nature of men’s-only talk. Behind closed doors, is it inevitably crass, boastful, and vulgar? Beyond that, does it involve boasts of non-consensual conquests? How common is it? Is it ever alright to be vulgar in private? Is it ever alright to boast of non-consensual conquests – indeed, to have them at all?

While “the locker room” has become spatial shorthand for the social space in which these conversations take place, “the vestry” (the room in which pastors put on their vestments) has scrambled to come up with a response. Most of the response has taken the shape of quickly condemning, not first and foremost the crass vocabulary, but rather the bragging about asserting unwanted sexual contact into social interactions with women. Some of the voices responding have been male – men who refuse to accept the unwanted advances of a male  politician assuring the

politician assuring the

populace that his own behavior wasn’t, and isn’t, harmful. Indeed, the best sermon I’ve ever heard on gender was preached by Tom Fuerst a couple of years ago, long before the current conversation reached fever pitch (listen here).

Some of the voices responding from the vestry have been female – women who cite their own experiences of sexual abuse and assault as evidence that what’s being said is excruciatingly harmful. “Wake up, Sleepers, to what women have dealt with all along in environments of gross entitlement and power. Are we sickened? Yes. Surprised? NO,” Tweeted popular women’s study author Beth Moore. “Try to absorb how acceptable the disesteem and objectifying of women has been when some Christian leaders don’t think it’s that big a deal,” she continued. Moore could hardly be characterized as an axe-grinding angry feminist; her books populate the shelves of conservative evangelical women. She is simply a woman telling the truth. One article from The Daily Beast illustrates the widening gap in the responses from evangelical women and some evangelical men, as their brothers in the faith determinedly look the other way.

It seems in our current cultural climate that the mic has picked up the twin identity crises emerging in the church and in the public square. It’s not so much that we’re at a crossroads as we’re at a demolition derby. At a time when deep down we would hope to put our very best people up for election as a government leader, we have one woman whose life has been sharply defined by her marriage to an infamous womanizer, and one man whose life has been sharply defined as an infamous womanizer.

In our public square, women across the country see two primary candidates for President of the United States: one has stuck with a serially unfaithful spouse. The other has regularly said horribly demeaning things to and about women while treating them as a fiscal and personal commodity in his business life. While there are other people on the ballot – thank goodness – the air time has largely gone to these two people. Both traditional political parties have put people front and center who communicate to women with their actions and words that this is the best we can do; this is the best we can expect; this is the best we deserve.

(Promoting the well-being and safety of women, by the by, is one of the most pro-life things you can do: after all, confronting a culture of sexual assault will inevitably lower the number of abortions performed. Not all abortions are chosen in response to sexual abuse, of course – no one would say that – but many women will never, ever bear the child who results from rape. Many women will never tell their abusive husband that there was another pregnancy, one he never knew about, after seeing their children sobbing in the corner. Do you want to protect the unborn? Go to bat against a culture of sexual entitlement.)

What the vestry ignores at its peril is the underground experience of sexual abuse by millions of women, as recounted in overwhelmed terms by an author who inadvertently opened the floodgates on Twitter. This comes after the soaring popularity of Project Unbreakable, a movement that started as a photography project, in which women – faces pictured or not – hold a simple sign with a quote written on it: the words they were told by their abuser.

While many stand-up men and professional athletes have come forward to exclaim vehemently, “that doesn’t happen in my locker room!” perhaps it would be more accurate to say, “those things aren’t said when I’m there,” which both acknowledges that their very presence could have an effect on the environment, and acknowledges that there is a subculture which does exist but in which they do not participate. It also leaves room for the idea that some of this subculture may have just gone underground: perhaps in many social spaces these conversations no longer take place.

But have you checked the average smartphone?

A couple of years ago we bought a smartphone from eBay. It worked great, came with a case and was delivered promptly. I eagerly began exploring it.

The previous owner had not been careful in removing his content.

I doubt the young women who sent the nude pictures to the previous owner ever suspected a pastor-mom would see them in their birthday suits. As far as I know, they sent them of their own free volition (though I don’t know whether they were over 18; they were very young, and if the previous owner was over 18, it could matter under federal law, concerning images of minors). I also doubt that the young women who hooked up with Mr. College Student (he appeared in several selfies) suspected that screen shots had been taken of their phone numbers under the names “Easy Bang” and “Crazy Whore.” In his phone, those were their names. Their identities. I also doubt one young lady would have suspected that a screen shot had been saved of text messages in which he apologized for the accident and offered to buy her the morning-after pill. (Somewhere, he had learned to cover his behind – though not the rest of himself, as one short video clip demonstrated.)

There was a whole locker room in one Samsung Galaxy.

If you want to give a youth group a heart attack, tell them your church WiFi has been hacked and all the content on their smartphones – including their internet search history – has just been downloaded to the secretary’s computer.

Did I say youth group? I meant congregation.

And the vestry will have a difficult time speaking into the public square if clergy smartphones are pocket-sized locker rooms.

But it’s not just about the abuse of status, influence and power in sexual interactions with women.

In truth, both the vestry and the locker room have been part of an ongoing national conversation for months now. Who can forget the nauseating news story that broke about white athletes sexually abusing a disabled black student in a small town high school locker room? What women of all colors are now testifying to, our black sisters and brothers have been saying for quite a while, as they’ve shared stories of discrimination, racism, and abuse: of being pulled over, followed around a department store, or questioned as to the ownership of their vehicle. What have they said? This has happened. This is happening. This will continue to happen unless we confront this reality.

Show me a person who is vocal about women’s rights or racial inequality, and I’ll show you someone who has had some deeply painful and personal experiences. Behind what may look like a “platform” is a story – or a lifetime of stories. It’s easier to talk about civil rights than it is to talk about the time you were called the “n” word. It’s easier to talk about women’s equality than it is to talk about the time you were groped.

So what trends will the mic pick up in our churches? In our locker rooms? What is the mic picking up in our public square? If we refuse to acknowledge the damage, then we have a lot of North American Protestant clergy who essentially are following the example of former Popes in turning a blind eye to the abuses happening in their vestries.

I am moved by stories of survivors: stories of women who climbed their way back from despair, self-loathing, and addiction. Women who – for better or for worse – have taught men to fear them. Women who confront their abusers and hold them accountable in court, so that whatever the verdict is, there will always be an asterisk in peoples’ minds.

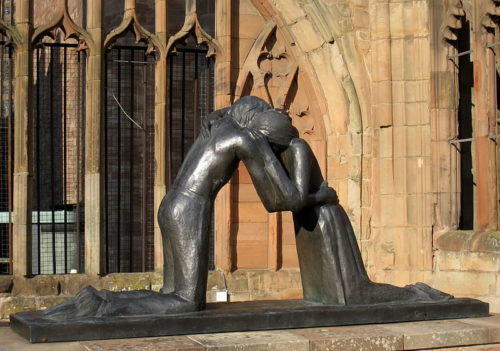

Recently I heard Dr. Andrew Thompson speak on acculturation, Constantine, and John Wesley. He expertly dissected the precarious relationship the church has had with the dominant culture in which it finds itself, pointing out that Wesley critiqued Constantine and the effects that came from Christianity being the religion of the empire. Rather than the empire becoming more Christian, the church became more like the empire.

It is dangerous to become complicit in the sins of the empire. There are many such areas; in this case, justice is at stake. How will we love our neighbors as ourselves? Dr. David F. Watson considered this question with insight and gravity recently here.

Most merciful God,

we confess that we have sinned against you

in thought, word, and deed,

by what we have done,

and by what we have left undone.

We have not loved you with our whole heart;

we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves.

We are truly sorry and we humbly repent.

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ,

have mercy on us and forgive us;

that we may delight in your will,

and walk in your ways,

to the glory of your Name. Amen.

Sometimes we need a space where there is new room for the Holy Spirit: space in our lives, in our schedule, in our church building, in our preaching, in our house.

For me, luckily enough – except it never seems to do with luck where new room is involved – this has been at the New Room Conference. In an age when marketers hope and pray that their ad campaigns will go viral, the Holy Spirit has seen that challenge – and raised it. It’s a potent reminder of how a little backwoods religion “went viral” all around the Mediterranean around 2,000 years ago. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge has nothing on the Third Person of the Trinity.

This September the gathering saw just its third birthday. Every year, it has doubled in size, causing organizers to have to change venues. Last year, with participants numbering around 800, it wasn’t too hard to find someone you wanted a quick word with. This year, at around 1,500, it was a bit harder, though the conference still managed somehow to have an intimate family feel – which is pretty remarkable, given that its participants represent a blend of denominations and regions.

Many people there have some kind of connection to Asbury Theological Seminary, but not all. (Seedbed Publishing, which sponsors New Room, is itself sponsored by the seminary.) Still, speakers and attendees came from a spectrum of experiences. Presenter Danielle Strickland hails from The Salvation Army (I couldn’t help but be thankful that she left her uniform at home). Andrea Summers has spent her ministry in The Wesleyan Church. Many other speakers were from the United Methodist Church, though Brit Pete Grieg is known for his work with the 24/7 prayer  movement. Bishop James Swanson preached a mighty sermon, though the presence of the Mississippi United Methodist underscored an area for growth: while there was racial and international diversity in the speaking line up, many (not all, but many) of the participants were noticeably Caucasian. If New Room truly wants to “sow for a great awakening,” it will inevitably find itself in a conversation on racial reconciliation at some point, because there is no awakening without the whole Body of Christ represented. We simply cannot receive it without each other. The Spirit won’t do it without all of us seeking healing together, in a posture of repentance and confession.

movement. Bishop James Swanson preached a mighty sermon, though the presence of the Mississippi United Methodist underscored an area for growth: while there was racial and international diversity in the speaking line up, many (not all, but many) of the participants were noticeably Caucasian. If New Room truly wants to “sow for a great awakening,” it will inevitably find itself in a conversation on racial reconciliation at some point, because there is no awakening without the whole Body of Christ represented. We simply cannot receive it without each other. The Spirit won’t do it without all of us seeking healing together, in a posture of repentance and confession.

Yet the seeds are here: Dr. Prabhu Singh from the Wesleyan Methodist movement in India spoke a powerful word. A panel of global representatives shared about what God is doing in different places around the world. One woman spoke about her ministry through mental health services to victims of ISIS brutality.

And I saw scholars, professors, pastors, worship leaders lying flat, face down on the ground in prayer. A prayer and worship service that was scheduled to be 90 minutes long went on for three and a half hours. It didn’t feel that long. Organizers handled it sensitively: there was ordered progression to the service, but flexibility as well. At one point someone leaned over to me and whispered, “this wasn’t on the schedule,” as Pete Grieg hopped up on the stage and exhorted everyone in the simple, powerful prayer, “Come on!” – asking the Holy Spirit to “come on,” to come down and transform lives, the world; goading our hearts to “come on,” to respond to God and wake up; and urging each other to “come on,” to keep going in the faith, to move forward together. It was during that service that somehow God plopped the desire of my heart in my lap, stringing together a nearly-impromptu covenant group that somehow seemed to just happen without a great deal of clarity about how it came together. Creating new room for the Holy Spirit, indeed.

The differences between New Room and other conferences are numerous, but one of the most pivotal differences in my estimation is the readiness to translate learning and growth at the conference into daily practice throughout the year, with its fostering of Wesley bands and its online platforms for group study that allow fellowship and growth to flourish regardless of geographic location. In this sense, it’s unique.

S0 – are you creating new room in your life for the Holy Spirit? Has your life created spiritual clutter? Do you need to sort and toss, mop and box up, or even just shove aside a pile of detritus to make just enough room to lie flat in prayer? Claim some space, now today: it doesn’t have to be much. Just enough time, or attention, or space to pray, “Come on, Holy Spirit…Come on…”

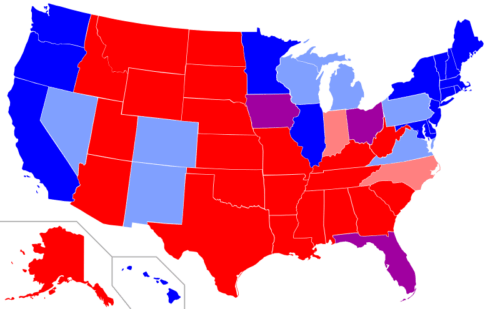

Regardless of your politics, but dependent on the plans of God, there will be a November 9, 2016. Do you know the day? It’s the day after the United States of America will choose between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. Between now and then, there will be a lot of debate, discussion, and Tweeting. But that day will come and, regardless of the victor, the church’s mission in the USA will continue.

Do you have a vision beyond November the 8th?

It’s hard to imagine a more polarizing political atmosphere, but Methodism may have already faced one. John Wesley, no supporter of democracy, was a sharp critic of the war between the colonies and the crown. On the other hand, Francis Asbury was the only British-born itinerant minister to stay in the colonies during the war. Asbury then remained for 30 more years, dying this side of the Atlantic, seeing the Methodist movement become a powerful force; ministering while there were arguments for individual freedom and corporate unity and conflicts between people of Irish and English descent. (For more information, see Bryan Easley, “The Leadership of Francis Asbury,” from Leadership the Wesleyan Way, Emeth Press.) Asbury realized that in spite of the short-term conflict, there would be a long-term mission.

Likewise for any Christians in the USA, without minimizing the importance and efforts that will lead up to November 8, there will be a November 9. There will be a mission that continues. And it is vital that missional seeds are sown even before November 9. This essay tries to outline the current political atmosphere in order to create empathy across political lines to provide space for a November 9 mission, an Asburian vision of a mission beyond the conflict.

Let me begin with a quick historical recount, helping to frame how we have arrived at today. The Modern period is captured in the Enlightenment, the intellectual spirit of the age that reason was the highest authority. It championed critical thinking. The Enlightenment promised a better life through better government, greater personal freedom, medicine, and scientific discovery. It delivered in huge ways. It produced a lot of wealth, health, and possibility.

Let me begin with a quick historical recount, helping to frame how we have arrived at today. The Modern period is captured in the Enlightenment, the intellectual spirit of the age that reason was the highest authority. It championed critical thinking. The Enlightenment promised a better life through better government, greater personal freedom, medicine, and scientific discovery. It delivered in huge ways. It produced a lot of wealth, health, and possibility.

But not as much as expected. And at times it ran aground. There was WWI and WWII. There was a Holocaust. The great advancements of the Enlightenment also created the possibility for great conflicts and great destruction and death. In light of these derailments, a new spirit, a Postmodern spirit, emerged in the late 20th century. Whatever this age would be, it would not succumb to the arrogance of the Modern period. It challenged the big, bad rationalist account of the world. It saw that all our understandings of reality (even scientific ones) are from certain points of view. It is not that each perspective is not true, but that each is incomplete.

To avoid this arrogant, rationalist, outward turn, the Postmodern period turned inward. Discovering truth in the objective world had led to the control and death of human beings—Berlin Walls, Israels/Palestines, concentration camps, industrialized work and abuses. The inward turn would not let other people discover what it meant to be human; it would allow—even demand—that each person find what it means to be human for him/her/vem/xer/perself. Here was the beauty of Postmodern movement: If the Modern period had the Enlightenment where “rationalist” was the only lens, then the Postmodern period would apply multiple lenses to everything. Each person has a lens and each lens is valid.

The multiple lens approach meant that we would value every lens we could identify: the lenses of being a woman, being gay, being Black, being poor, being an immigrant, being native, and so forth. The more lenses, the better. Many lenses proved to sharpen focus and to examine things from multiple points of view, holding the potential for growth in knowledge, understanding, and progress. However, one unnecessary result was that the value of those sociological lenses that were previously established (wealthy, white, male) were now disregarded—officially, at least. Those lenses were to blame for violence, abuse, and control. Let’s bring this back to the political realm. In politics, the advantage of having a lens that was previously unconsidered was called being an “outsider.” If you weren’t part of the “political establishment,” then you brought a fresh perspective and a citizenry would benefit from such leadership.

Through all of this cultural development, four very important things (among others) happened:

1. Global migration

2. 9/11 and global terrorism

3. Social media

4. Seven Billion Cell Phones

Suddenly, things that were happening all over the world were brought not just into our homes, but into our faces; and not from a framed perspective by news media, but from multiple perspectives from various amateur  videographers; and not only were these perspectives from other countries, but they were shared by other people who now lived up the road from us and who worked next to us and who received a burger from us at McDonald’s and who fixed our computer and who built our house and who married our Dad, daughter, or cousin; or who became our MP, Senator, Governor. Suddenly, diversity was not simply a theory that could help bring beauty, technological advancement, and new restaurants; it became a next door reality that became, at least for some people, scary. The world that was imagined in the 1980s and 1990s—a world of peace through multiple lenses—was being threatened. The promise that some had read into Postmodernism—a progressive peace through diversity—was being challenged. Rather than peace, there was more war, closer war, unframed war.

videographers; and not only were these perspectives from other countries, but they were shared by other people who now lived up the road from us and who worked next to us and who received a burger from us at McDonald’s and who fixed our computer and who built our house and who married our Dad, daughter, or cousin; or who became our MP, Senator, Governor. Suddenly, diversity was not simply a theory that could help bring beauty, technological advancement, and new restaurants; it became a next door reality that became, at least for some people, scary. The world that was imagined in the 1980s and 1990s—a world of peace through multiple lenses—was being threatened. The promise that some had read into Postmodernism—a progressive peace through diversity—was being challenged. Rather than peace, there was more war, closer war, unframed war.

In light of this quick historical recount, let me frame the two political candidates who will be voted on November 8:

1. Donald Trump. The Republican nominee is the result of some who want to be heard again, whose lenses were discarded when others were rising in importance. President Trump represents for many the white, male voice. I know some think the white, male voice has never stopped being heard, but their perspective has lost all power. Remember the credit crunch? Don’t trust the bankers! Down with CEOs! Has anyone ever heard of someone studying “Masculine” or “Man Studies” in University? Mr. Trump is all of the things that capture what people thought stopped being important in the Postmodern turn—and he is a political outsider. Some people remain surprised he has a chance at being President. Quite the opposite is true. If he—the wealthy, white, male, political outsider—hadn’t become an option for President, we should have been surprised.

2. Hillary Clinton. The Democratic nominee is the politician who has moved with the spirit of the age. She works (very hard!) to use every lens that she might encounter—every gender, every woman, every sexuality, every economic sphere. But here’s the irony: The belief that one can hold every perspective means a rejection of those perspectives which do not believe certain lenses exist or that certain lenses are helpful or that holding every lens is advisable or that do not share desires that people with other lenses do. This conflict results in, say, a basket of deplorables problems. Suddenly, lots of people feel unheard, unconsidered, mistreated, and disrespected. Why didn’t they get to participate in what it meant to be human like everyone else did? Why doesn’t their lens count anymore?

Now, note the irony. Mrs. Clinton is herself a fresh lens—the first potential woman president—who purports to value multiple lenses, but she is also the consummate political insider. She is the archetype postmodern politician.

On November 9, the issues that were used to frame opponents, reject candidates, and solidify voting blocs will remain. The election will be decided; the mission will continue. Will we have any Francis Asburys who can see beyond the conflict, to craft the next 30 years of mission advancement? Will we have any Francis Asburys who ministered in the midst of conflict, gave up his status, “[e]mbracing humanity [by] being vulnerable in relationships, finding appropriate ways to connect and relate to others, and learning from their perspective”?

Let me offer several kinds of persons that Asbury might relate to in our day:

People whose previously strong, bustling city has turned to garbage and decay over the last 30 years, while no one has cared to listen to their opinion;

People whose home as a child was far better, safer, and joyful than the house they’re providing for their own children;

People who have started feeling increasingly heard and valued in the last 20 years but who fear it will all be taken away;

People whose life and meaning have been based on ancient values that are now increasingly threatened while they are called hateful and legally forced to separate their personal convictions from how they make their living;

People who have escaped cycles of poverty but who still see their extended family stuck in drug abuse and economic poverty; who worry that they might be drawn right back into these cycles once their playing career is over.

These are people often on different sides of the political fence, but who stand before God’s people for missional service. Will we have any Francis Asburys on November 9, people with a vision for a future beyond the conflict? People with courage of conviction that Jesus is raised from the dead, is the definitive word of God, and whose lives have been transformed and empowered by the Holy Spirit, yet people with humility to sacrifice their status, empathize with another, and relate to those whom God brings into their lives?

Asbury had a vision beyond the war and we are part of his vision bearing fruit. May we emulate his ability to see beyond out immediate conflicts, as well.

If you or I think of a laser, we probably have a mental image of what we might colloquially call a concentrated beam of light, whether it’s used recreationally like in laser tag or a laser light show, or practically like in an eye surgery or in cutting material. You might even picture the powerful ray from the Death Star in Star Wars or a light saber from the same series (though sadly, according to a television special I saw once, a light saber would be almost impossible to construct from the actual current scientific standpoint). One classic James Bond film includes a memorable scene in which the famous spy has a close encounter with a shining laser beam slowly inching towards him as he is tethered helplessly on a table.

In other words, while some lasers are more powerful than others, their narrow beams continue to fascinate us and new applications will probably be explored for decades or centuries to come.

Which leads us to holy love.

At the recent New Room Conference (a place you need to be next September), I picked up a slight, pocket-sized Seedbed Seedling volume by Dr. Joseph Dongell simply titled Sola Sancta Caritas (“only holy love”), available digitally for free here or in a handy little hard copy here. (The Seedling’s diminutive size makes them perfect for a church resource table or kiosk.) Dr. Dongell is a longstanding biblical and Greek scholar and professor. In Sola Sancta Caritas he offers a masterful survey of the Wesleyan holiness movement’s outcomes, the nature of Wesleyanism, robust examples of the centrality of the notion and practice of holy love in Wesley’s writings, and what holy love does and does not encompass.

Not bad for a thin pocket volume 45 pages long.

While Dongell examines the trends or waves of Wesleyan thought and scholarship, he draws his own startling conclusions from a full immersion into Wesley’s sermons, journals and letters (found on page 15).

In reading through Wesley for myself, it seemed to me that love rushed through all fourteen volumes like a tsunami. My handwritten index tracking substantive references to love in each volume had taken the appearance of a dense forest. It seemed that Wesley was standing on his head and shouting to draw attention to love.

Among other well-chosen quotes, Dongell highlights this one from Wesley’s sermon On Patience:

From the moment we are justified, till we give up our spirits to God, love is the sum of Christian sanctification; it is the one kind of holiness [there is, the degrees of which are simply differences] in the degree of love.

Love is the sum of Christian sanctification? This, Dongell concludes, stands in contrast with the revivalist upbringing he cherishes but of which he acknowledges the limitations. In the North American 20th century holiness movement, it was purity and power emphasized as the effects of sanctification.

By appreciating the full impact of Wesley’s emphasis on holy love, Dongell redirects our Wesleyan Methodist attention into sharp, concentrated focus: holy love is narrow yet far-reaching, both penetrating and illuminating, something that can be familiar and safe or deadly in its aim.

Holy love is like a laser. It is anything but saccharine or weak. It is anything but flimsy or peripheral. It is not an addendum, not an afterthought. Holy love, laser-like, may appear powerful and pure, but those are descriptors, not its essence. Holy love, Dongell clarifies, is not, “general human intuition.” Neither, he stipulates, is it good works. Holy love finds its origins not in humans, but in God. Holy love will not pop up automatically from our own nature; Dongell ensures our awareness that it is the gift of God. And, “the infusion of God’s love within us produces holiness as its natural outcome.” Again, we see that we are called to be more than we are able, we can receive what we need to be able, and that being like Christ through an infusion of God’s love will produce the side effect of holiness.

So what makes a laser a laser? Why isn’t like other light, shining gently from a lamp? The very briefest and most basic description asserts that a laser, “emits light coherently. Spatial coherence enables a laser to focus to a tight spot.” As far as this non-physicist can tell, coherence has to do with correlation between waves.

So what makes a laser a laser? Why isn’t like other light, shining gently from a lamp? The very briefest and most basic description asserts that a laser, “emits light coherently. Spatial coherence enables a laser to focus to a tight spot.” As far as this non-physicist can tell, coherence has to do with correlation between waves.

Now of all his activities, of all his travels and writing and busyness, one thing could easily describe Wesley: his focus. In fact his focus was so severe that one may quickly surmise an armchair diagnosis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Weighing your food intake at every meal aside, what Dongell hits on is Wesley’s laser-like focus. Sola Sancta Caritas – “only holy love” – is what Wesley’s methodology, his theology, his ecclesiology boil down to.

Miners don’t go to church? Take your preaching into the fields to them: holy love.

People don’t have access to rudimentary health care? Publish a common-sense pamphlet: holy love.

Christians floundering in their zeal for their faith? Band them together with likeminded Christians, like the Moravians did: holy love.

How often should Methodists take the Eucharist – that tangible reminder of the embodiment of Christ’s love? As often as possible: holy love.

Methodists on the American frontier not getting the Eucharist? Ordain your own ministers and send them: holy love.

Someone dragging down a group by willfully neglecting the guidelines for covenant together? Suspend them: holy love.

Like a laser.

Now the question remains: how well are we known for our focus? For our laser-like intensity? Should Methodists be the most undistracted people on the planet?

Whether the topic is famine relief or preaching, criminal justice reform or small group programs, funeral dinners or church landscaping choices, what must characterize it all, if it is to be distinctly Wesleyan Methodist?

Holy love.

Leave out holy love and you may have solid humanitarian work, efficient discipleship programs, even biblically shaped sermons, but you won’t be a Christian following Jesus in the company of the Wesleys. The fullest picture we have of holy love is the life of Jesus Christ. No wonder Wesley emphasized the Eucharist over and over again: to live like Christ is to live holy love. We need the holy love of Christ through Holy Communion, to taste it and mull over it, to hear, “the Body of Christ, broken for you.”

A laser can encompass a great deal. Part of the scientist’s protest against the idea of constructing an actual light saber was not that it couldn’t be built, but that it would be impossible to limit the laser to a specific field: imagine turning on a light saber and having the “blade” extend all the way out to the moon and beyond. Nonetheless, as noted above, a laser is inherently limited. Its internal coherence focuses it (again, speaking as a layperson, not a physicist). And so there are some things lasers will always encompass and some things lasers will never encompass.

How like sanctification.

We lose our way if we focus on result instead of source. We lose our way if we get distracted with one program or topic at the loss of our most basic reason.

Recently I spoke on just this subject with a camp meeting preacher. Would it be a healthy corrective, I suggested, if the message of holiness was always tied back to the Second Person of the Trinity? In many Wesleyan holiness contexts holiness is preached in the context of the Third Person of the Trinity. Rightly so. But the Holy Spirit does not just infill humans as a kind of sanctified cul-de-sac, detached from the revelation of Christ. The Holy Spirit always witnesses back to Christ, revealing Christ, empowering Christlikeness. The Holy Spirit tells the story of Christlikeness through us. This distinction finds its shape in systematic theology but we see Dongell illustrate the distinction well through the contrast of power and purity and holy love.

It is not the Holy Spirit’s job to make us pure and powerful. It is the Holy Spirit’s job to make us like Jesus. As it  happens, Jesus is pure and powerful. But the Spirit is constantly in a dance to reveal Christ, to shape us into “little Christs.” In this sense, C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity made a wonderful Methodist:

happens, Jesus is pure and powerful. But the Spirit is constantly in a dance to reveal Christ, to shape us into “little Christs.” In this sense, C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity made a wonderful Methodist:

Now the whole offer which Christianity makes is this: that we can, if we let God have His way, come to share in the life of Christ. If we do, we shall then be sharing a life which was begotten, not made, which always existed and always will exist. Christ is the Son of God. If we share in this kind of life we also shall be sons of God. We shall love the Father as He does and the Holy Ghost will arise in us. He came to this world and became a man in order to spread to other men the kind of life He has — by what I call “good infection.” Every Christian is to become a little Christ. The whole purpose of becoming a Christian is simply nothing else.

If you are a Wesleyan Methodist, are you known for your laser-like focus on holy love? On the kind of love that may cauterize and burn, may illumine and dance, may direct and heal? What would it look like if you brought every church activity under the microscope of holy love? Maybe all of the programs would stay the same, maybe not. Maybe the only thing that would change is the way in which they are carried out – and why.

Through the Holy Spirit, God, make us like Jesus: and empower our focus to be stark and laser-like, so that we are known as people with internal coherence. May our waves find their correlation in you. And let us shine like lasers.