Humans are expert excuse-makers.

“Well, GOD, the woman you gave me tempted me, so…that’s why I didn’t listen to you when you told me not to eat anything from that tree.”

“I know I’m not supposed to cut my hair, but…I mean, have you seen Delilah? I’m only human.”

“I’d love to follow you, Jesus, but I have family obligations and an urgent to-do list first. Let me take care of those things and then I’m totally on board.”

“I’ve followed all those commandments since I was a kid, and now you’re asking me to give up my hard-earned wealth in order to follow you? How is that fair? Surely I can have both?”

“Learning with the men is all well and good, but Jesus, are you going to let her shirk the duties literally all other women manage? I’m in here in the kitchen and I’m happy to be, but I need some extra hands! After all…this dinner is for you…”

“Who, that guy? No, no, I wasn’t one of his disciples, I’m just hanging out here. You must have me confused with someone else. No, *&#$, I’m telling you, I don’t know Jesus!”

You and I can find a multitude of ways to make excuses for ourselves, and just as dangerously, for each other.

“He’s a great leader, so we shouldn’t hold his past indiscretions against him. After all, we’ve all sinned and fallen short of the glory of God, so we shouldn’t expect more from our pastors than we do anyone else.”

“She would face a lot of resistance from peers and family members, so while she did a great job preaching last Sunday, let’s not pressure her to enter pastoral leadership; there are other places she can serve, and we’ll be doing her a favor to protect her from the resistance she might encounter.”

“I’ve fought long and hard to get to where I am. I’m finally a voice at the table. If I mentor other underrepresented people, are they going to take the opportunities I’ve worked so hard for? Is she my ally – or my competitor? Chances like this are few and far between. Someone else will give her a leg up. I have enough on my plate already.”

“It’s just really hard to find minority speakers, we’d love to have some on the lineup, but we’re just not aware of many who have the experience for this kind of setting and this size of a crowd.”

“If I accept that speaking invitation, they’ll just try to use me as a token representative. I’m sure it would be a waste of time. It would just be settling their uneasy consciences. I don’t think that’s how God wants me to use my time right now. I can make more of an impact somewhere else.”

“Those women have troubled pasts, so obviously we can’t take their accounts seriously. I grew spiritually under his leadership, so it’s hard to imagine he would’ve done those things to kids. This is just Satan attacking him and his ministry. Now more than ever, we need to rally around him and pray for him.”

Beware the excuse that lets you off the hook, or lets your friends, your ideological companions, or your heroes off the hook. If you have to jump through some hoops in a way you would never accept from your opponents, your ideological adversaries, or those you disdain, let that be a red flag: abandon hope, all ye who enter here.

Recently I read an observation from someone on Twitter (sorry, anonymous, I can’t remember who you were). He simply said that across conservative and liberal spectrums, religious and secular, red and blue, that in North America, God is busy unmasking our hypocrisies. It occurred to me that unmasking hypocrisies is a grace – a gift. Many in the Wesleyan Methodist family have been praying for a great awakening. But is awakening possible without first coming face to face with the depth of our own sin, faults, blindness, and excuses?

John Wesley didn’t think so. In his “Letter on Preaching Christ,” he noted,

After more and more persons are convinced of sin, we may mix more and more of the gospel, in order to “beget faith,” to raise into spiritual life those whom the law hath slain; but this is not to be done too hastily neither. Therefore, it is not expedient wholly to omit the law; not only because we may well suppose that many of our hearers are still unconvinced; but because otherwise there is danger, that many who are convinced will heal their own wounds slightly; therefore, it is only in private converse with a thoroughly convinced sinner, that we should preach nothing but the gospel.

In this context, he is counseling on how to preach to believers and unbelievers; and he clarifies that while preachers must preach hope, that hope can only truly be received after a person is clearly convinced of the depth of their own need for it. In other words, preaching to show how far off the mark humans generally are must come before we can effectively preach the scope of the promises of a loving, pursuing God.

In other words, while awakening is the satisfying part, unmasking excuses and hypocrisies in both believers and unbelievers must come first.

Wesley continues by pointing out that preaching that celebrates the love and goodness of God without confronting the twists of the inner heart has done considerable damage in different parts of England:

This is the plain fact. As to the fruit of this new manner of preaching, (entirely new to the Methodists,) speaking much of the promises, little of the commands; (even to unbelievers, and still less to believers;) you think it has done great good; I think it has done great harm.

The Spirit of God is an equal-opportunity hound nipping at our heels. The Hound of Heaven doesn’t pursue “them” without also pursuing “us.” And part of this conviction of our souls appears when we attempt to abandon common sense and morality as if they are divorced from the revelation of Scripture; as if somehow they are dispensable, unrelated to the Word of God. But of course the “Hound of Heaven” will not let this cognitive dissonance continue unchallenged indefinitely.

God never intended Scripture to be used as an excuse to abandon common sense and general ethics. Even Satan twisted the use of Scripture during the temptation in the wilderness. Jesus actually preached against this tendency when he pointed out, “you think loving and forgiving your friends and family is a virtue? Even crooks and pagans do that.” In other words, “basic decency available through prevenient grace and general revelation of God’s goodness in the world isn’t something you should brag about. People of other religions or no religion love their families and forgive their friends.” He continued – “but I say to you, love your enemies and pray for people who persecute you and make your life miserable.” (Matthew 5:43-48, Elizabeth Version)

Jesus cuts through their feeble defense at their own righteousness like a hot knife through butter. “Don’t brag to me about the number of truckloads of supplies you sent out of your abundance to citizens of your own country going through a natural disaster. The mosque down the street did that too. So did a bunch of atheists. Instead, tell me what you’re doing to love the opponents, threats, enemies, and irritants in your life, locally, nationally, and globally.”

The Holy Spirit, the Hound of Heaven, not only uncovers the areas in which you and I make excuses for why we can ignore basic common sense and morality; the Holy Spirit also stays in pursuit of us, moving beyond general common sense and ethical norms, pushing us further and further towards the model of Christ, so that, far from relying on our laurels of meeting basic morality codes, we are hounded to live closer to the image of Christ, pursuing peace with our enemies, loving people who have wronged us, proactively serving people who despise us, and abandoning our right to be seen in the right.

God save us all, liberal and conservative, Republican and Democrat, religious and secular, from “healing our own wounds – slightly.” We cannot any of us afford to live in the stench of our own excuses.

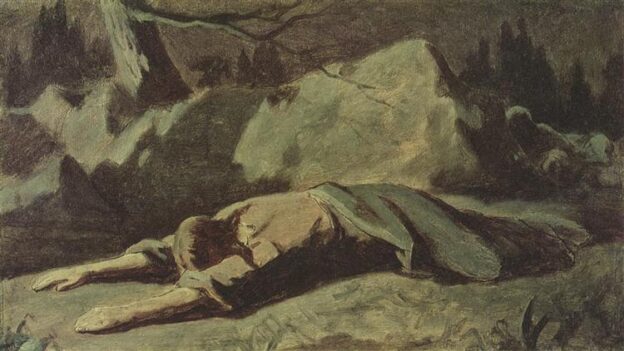

As Francis Thompson wrote in the first portion of his famous poem “The Hound of Heaven” (that deeply influenced G. K. Chesterton and J.R.R. Tolkien),

I FLED Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.

Up vistaed hopes I sped;

And shot, precipitated,

Adown Titanic glooms of chasmèd fears,

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

But with unhurrying chase,

And unperturbèd pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

They beat—and a Voice beat

More instant than the Feet—

‘All things betray thee, who betrayest Me.’

In your relentless, pursuing grace, o God, let us get tired of attempting to outrun the discomfort of coming face to face with you.