Recently, I heard a church leader describe the instinct to “drop Facebook napalm” in an online debate. What a great image. Our cultural currency right now isn’t the American dollar or the speculative Bitcoin: it is outrage.

Outrage is addictive, and it’s so easily justified: we sanctify it with the word “prophetic” or the word “faithful.” God calls us to be prophetic, to offer a bold word against corruption or misused power or oppression. God calls us to be faithful, to offer truth against confusion or heresy or trendy emptiness. Outrage energizes us when we’re tempted to lean back in apathy; it gives us a sense of purpose or righteousness when we’re feeling pointless or despicable.

Blessed are the outraged.

Even now, a few readers will want to protest about how important and urgent and warranted their causes are.

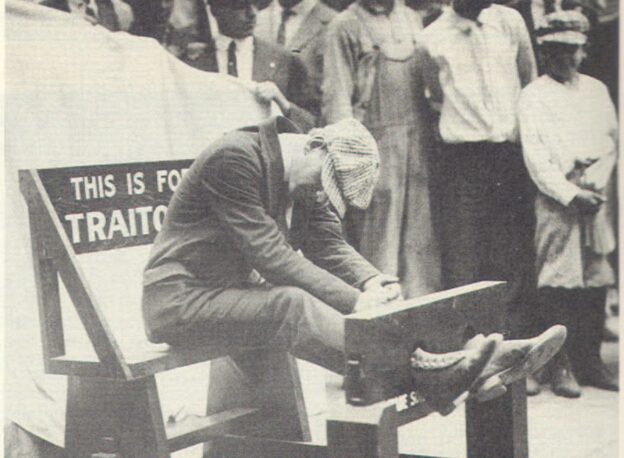

Of course they’re important and urgent and warranted. That’s not the point. Confrontation doesn’t require public shaming. If it does, we’re doing it wrong. Confrontation doesn’t require we put opponents in public stocks and heave a well-aimed rotten vegetable viral hashtag at their head. Even furious anger and indignation at injustice doesn’t require public shaming.

Do we think that shaming someone will lead to repentance? That hearkens back to The Scarlet Letter. Shaming someone else rarely calls forth transformed behavior in them – or in ourselves. Shaming another person gives us the vaulted position of judge, jury, executioner, and obituary writer without having to get our hands dirty by investing in their lives.

The great irony of our time is that we chant “don’t judge” while giving into the outrage that is comfortable shaming opponents in the public square. Maybe we chant “don’t judge” because we’re so busy shaming others; in repeating “don’t judge,” we’re trying to fight our worst internal instincts: that of devouring each other.

Our motto would serve us better if it were, “in your judging, be kind and embody humility.” And that really captures the heart of the Gospel of Jesus Christ better. Judging isn’t the problem: shaming is.

We are called to love and pursue Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, ancient transcendentals which have called thinkers to study logic, aesthetics, and ethics. If our outrage turns ugly, we may fight for goodness with confrontations of the truth, but we will have lost the grace of beauty, and we will have lost. If our outrage turns to ethical fragmentation, we may fight orderly and with grace, but we will have lost the grace of goodness and clear moral direction. If our outrage turns incoherent, we may fight attractively for the good, but we will have lost the order and reason and sense of truth outside of our isolated cause.

We all discern: we all judge. We judge whether or not a dairy product is good or has gone bad, we judge whether one dog is closer to the ideal of its breed than another, we judge whether a habit has a positive or negative outcome on our child, we judge whether a leader takes us closer or farther away from a goal we judge to be worthy of pursuit.

We all speak: we all confront. We confront a cashier about a mistake in our favor or against our interest, we confront a business about a mishandling of our package or our order or our service, we confront discomfort in our own lives through healthy action or unhealthy avoidance, we confront strangers, acquaintances, friends, and family members online.

What we don’t all need to do, of necessity, is to shame. A call to repentance is not inherently or of necessity shame-causing. There is no order, no beauty, no goodness in shaming: there can be order, beauty, and goodness in discernment, judgment, or confrontation.

And not all feelings of shortcoming or inadequacy are bad. I ought to feel inadequate to pilot a nuclear submarine. I ought to feel inadequate to trade stock at the New York Stock Exchange. I ought to feel inadequate to administer anesthesia to a surgery patient.

And I ought to feel a sense of shortcoming if I engage in a pattern of behavior that hurts myself, others, and God. I ought to feel a sense of shortcoming if I smack a child on the face. I ought to feel a sense of shortcoming if I lose my temper and berate a stranger.

If we are dressing up our outrage as “prophetic” or “faithful” but we don’t have love, we’re a sounding brass, a clanging symbol. Love bears all things and hopes all things. It’s hard to persevere in bearing all things and in hoping for redemption in the midst of shaming someone.

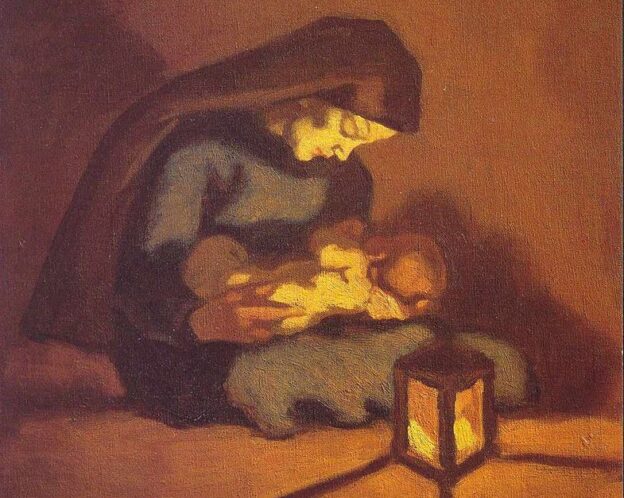

Loving acts are beautiful acts; they are good acts; they are true acts. They shout the beauty of being a person created in God’s image, they shout the goodness of peaceful confrontation, they shout the truth of our own worth and inadequacy. To proclaim justice does not require arrogance on our part. But shaming another human being requires a certain amount of arrogance within ourselves.

Jesus is Truth – the Word, or logos made flesh. Jesus embodied and spoke truth. Jesus’ incarnation gave Reality itself fingerprints. So when Jesus confronted others, it was almost always because they were busy shaming instead of confronting. The religious leaders weren’t just confronting the woman caught in adultery, they were deliberately shaming and humiliating and depersonalizing her. To shame a person is to remove the dignity of being human from them; and if we have removed their humanity, we are no longer bound to treat them with respect and care. Jesus didn’t shame the shamers: Jesus discerned – that is, judged – their motives, and he confronted them. Repentance, Jesus knew, didn’t require shaming a person, even if it did sometimes require judgment and confrontation.

Truth is beautiful: so communicating truth, however confrontational, cannot be done in a way that smears the inherent beauty within our fellow humans.

Truth is beautiful: so communicating truth, however confrontational, cannot be done in a way that smears the inherent beauty within our fellow humans.

Consider, in closing, these reflections from artist Makoto Fujimura, in Refractions: A Journey of Faith, Art, and Culture –

Why art in a time of war? Jesus stated, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called sons of God” (Matt 5:9). The Greek word for peacemakers is eirenepoios, which can be interpreted as “peace poets,” suggesting that peace is a thing to be crafted or made. We need to seek ways to be not just “peacekeepers” but to be engaged “peacemakers.” Peace (or the Hebrew word shalom) is not simply an absence of war but a thriving of our lives, where God uses our creativity as a vehicle to create the world that ought to be. Art, and any creative expression of humanity, mediates in times of conflict and is often inexplicably tied to wars and conflicts.

The arts provide us with language for mediating the broken relational and cultural divides: the arts can model for us how we need to value each person as created in the image of God. This context of rehumanization provided via the arts is essential for communication of the good news. Jesus desires to create in us “the peace of God, which transcends all understanding” (Phil 4:7), so that we can communicate the ultimate message of hope found in the gospel, the story of Jesus, who bridged the gap between God and humanity to a cynical, distrustful world.

The Outraged will wear out; Blessed are the peacemakers.

This extraordinarily self-confident priest is best known as the vicar of Baghdad, leader of a church in the chaos outside the protected Green Zone. He made his offer last year as the terrorist forces threatened to take the city. Did he get a reply?

This extraordinarily self-confident priest is best known as the vicar of Baghdad, leader of a church in the chaos outside the protected Green Zone. He made his offer last year as the terrorist forces threatened to take the city. Did he get a reply?