I’m a historian by training. It is what I do and how I think. This training orients my own spiritual formation as well. I think about the past as a way to make sense of God’s faithfulness and to consider my Christian duty as well as others’.

Thinking like a historian tends to consider how we narrate our stories and what we can learn from them. Stories are instructive. They give us models of sainthood that we can emulate. They also give us examples of failure, serving as a call to live up to God’s call to be holy.

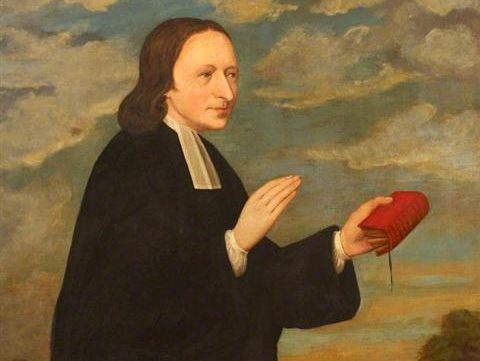

That said, sometimes we fall into a trap in our way of thinking about the past, especially the history of our own Christian tradition. For me, that’s the Wesleyan tradition. When I read some of the leading historians of the Wesleyan tradition, I am struck by a common theme. They like to tell the stories of the founders of the tradition. There is a common trope that we focus on the ministry and theology of John and Charles Wesley and their general legacy among the people called Methodists and their derivative denominations. You can trace the founders’ influence: Wesleyans look to the legacy of racial and social justice in the protests by Luther Lee, Orange Scott, LaRoy Sunderland, and Lucius Matlack. Free Methodists revel in the populism of Benjamin Roberts. Nazarenes relish the emphasis on personal holiness and welfare for the poor promulgated by Phineas Breese. And our brothers and sisters of color in the United Methodist, AME Church, CME Church, and AME Zion denominations look to the leadership of Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and others to carve out space for African Americans in the face of discrimination.

Each of these individuals ought to be appreciated for their contributions to the Wesleyan movement and for highlighting the need for new emphases of piety and justice, which are hallmarks within Wesleyan Methodism.

But what happens when we focus exclusively on the work of the principal figures in the establishment of these denominations? Might we run the risk of what one historian referred to as “founders chic[1]”? It’s a term used to underscore an obsession with the founders of a movement—initially referring to the generation of men who ushered the North American colonies through independence and then into a constitutional, democratic republic. The problem, critics note, is that such strategies of writing about the past tend to focus primarily on white men of social and economic privilege, thus elevating their privilege even further. Another important criticism is that founders chic is a top-down approach to historical writing that privileges the contributions of social elites, typically white men of political or cultural influence. Thus, social historians of the mid-twentieth century have attempted to counter this approach by writing history from the bottom-up, from the perspective of lesser-known actors in history or from the perspective of broad sociological patterns in the past.

There is much to be done with the social history of the Wesleyan tradition. It allows us to look at other actors in history, particularly those frequently not represented in our denominational histories. Specifically, we begin to look at the roles that laity, women, people of color, and lesser-known clergy played in shaping the contours of Wesleyan Methodism in smaller pockets of denominational and devotional life.

We can appreciate what the Wesleys did to inspire a new movement of personal and social holiness. We can affirm holiness as we read it in the Bible, and as Wesley’s sermons have shaped our doctrine. However, the founders chic trend in historical writing about the Wesleyan tradition zeroes in on John and Charles Wesley. But here, I argue, are two major reasons why we should move beyond the concentration on John and Charles.

The first is a matter of time. John Wesley’s conversion was nearly 300 years ago, and some of his greatest theological contributions were written more than 250 years ago. He was birthed from a different era, often trying to match his theology with the philosophical writings of the Enlightenment and tackling problems arising from England converting from an agrarian society to a mercantilist empire to an industrialized society. Additionally, there are some glaring red flags in his anthropology with his less-than-complimentary, if morphing, views of native peoples, including Africans and Native Americans. Should we continue to think like Wesley thinks on some of these things? Certainly not.

The second matter is space. While Wesley’s movement extended well beyond the British Isles, we often overlook the local contextualization of Wesleyan Methodism in those parts of the world where it spread. Here I will speak to the United States. In Wesley’s own lifetime, Methodism became a standalone denomination in America. Under Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury, it shifted from a connection of like-minded pious Anglicans into a distinct religious identity. And as such, it developed from a sect within Anglicanism into a church in its own right. And that is a story that should concern us more, at least in America. The flourishing of Wesleyan Methodism and its spin-offs provides narrative contours that intersect momentous epochs of American history for which John and Charles Wesley had no direct influence.

Furthermore, when we don’t look at how Wesleyan Methodism developed in America, we fail to understand what conditions gave rise to the further splintering of the Wesleyan tradition in the United States. How did the O’Kelly schism of the 1790s raise issues that parallel those of Roberts in the 1850s ? Or how did a movement committed to social justice find itself so deeply complicit in slavery, the most heinous injustice in American history? That complicity gave rise to the AMEC and AMEC Zion churches as well as, later, the Wesleyan-Methodist Connection in the 1840s. It also contributed to the fracturing of Methodism into its northern and southern branches, a division that lasted more than 90 years. And when it re-merged in the 1930s, it did so without resolving the racial injustice of Jim Crow. How did the Methodists of color resist Jim Crow with a specific Wesleyan accent? How did the evolution of Methodism in the later nineteenth into a mainline denomination that sought to buttress a white middle class status quo foster new holiness movements in the 1880s and 1890s that broke away from the Methodist Episcopal Church to emphasize personal piety and concern for the poor? And as Methodism further developed into a liberal mainline denomination in the twentieth century, how might the conservative voices have felt slighted, organizing within Methodism to challenge what they perceived as liberal trends far afield from biblical and holiness teaching?

There is a wealth to be explored by examining the histories of Wesleyan Methodism that move far beyond the founders of Methodism or its descendant denominations. When we apply the skills of writing the history of Methodism from the bottom up, we gain an appreciation for another cast of historical actors and social conditions that gave rise to a distinctly American Wesleyan accent within Methodism.

[1] https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2003/09/founders-chic/302773/

[2] Like many Enlightenment thinkers, Wesley sometimes used descriptors like “savage” or “heathens” when communicating about native peoples including Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans like Celts and Finnish people. Later descriptors were more nuanced, such as in “Thoughts Upon Slavery,” which was a contextually bold defense of African Muslims (“Mahometans”) against the evils of the slave trade, the practice of which comprised the subject of his final letter before his death that he wrote to abolitionist William Wilberforce.