Epiphany: A Kaleidoscope of Mercy

We have traveled (less this year than others) through the days of Christmas feasting, arriving like the Magi at Epiphany. This is a blessing on a prosaic scale: as a child, Christmas was one day, not 12; and given all the build-up, something seemed off about abandoning festivities so quickly. The cadence of maneuver through 12 days makes more rhythmic sense in the ebb and flow of liturgical tides.

Epiphany restores to the Magi their rightful place in the sequence of the Nativity, tilting them a bit farther away from the rest of the living room Nativity sets. At a distance, the stargazers are not quite elbow to elbow with the shepherds, whose eyes were sometimes less on nighttime stars and more on the threats of their immediate surroundings. The shepherds and sheep figurines may be clustered around the Christ-child; but the Magi are still on their way.

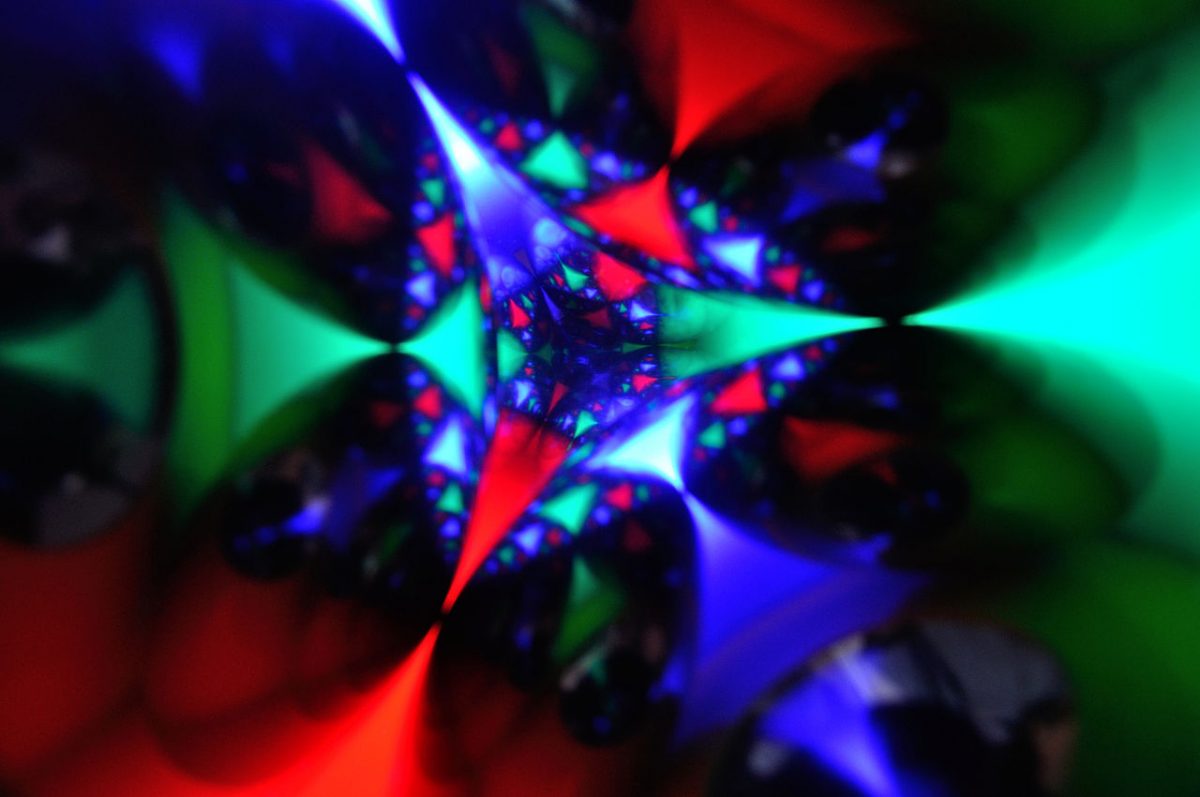

The mercy of revelation – because revelation from an all-powerful, transcendent God of love is mercy to humans who would not be able to grasp God’s nature on our own – may vary in timing. Like a gently shifted kaleidoscope, God’s mercy appears in one set of colors and shapes, then slides and trickles into another as time passes and the kaleidoscope is moved. The tints and outlines of mercy appear to animal caretakers keeping watch at night; the kaleidoscope tilts, and the same mercy appears, this time to star-gazing scholars – to Gentiles.

Epiphany is a swirl of colors and shapes that, when tilted again, reflects the mirrored patterns of mercy in John 4. Here, we watch Jesus as he “has” to go through Samaria; we watch his disciples go into town to buy lunch; we watch him talk with a woman, a Samaritan woman, by a well. We watch him disclose to her what he rarely verbally affirmed – that he is in fact the Messiah. She doesn’t know about the myrrh and frankincense and gold that strangers brought to his parents when he was two, but she receives the same mercy that the Magi received when they brought their gifts. When the disciples return with lunch and encourage Jesus to eat, we see him respond, “I have food to eat that you know nothing about.” In truth, he is revealing that he has mercy that they know nothing about.

To draw from his own well of hidden mercy – this is why Jesus had to go through Samaria. At the time of his birth, what attention did the priests and scribes pay to – astronomy? Yet there was mercy hidden from their view but written in the stars.

“I have mercy you know not of.” A flash, blinding light – otherworldly beings appear to shepherds who smell of dung. An appearance in the night sky of a new celestial body captures the attention of foreign mages. A cleared throat and polite voice sounding young and ancient at the same time asks for a drink of water at a well at mid-day.

The kaleidoscope turns; the mercy of revelation remains.

Is revelation always a mercy? Yes – even if it is our undoing. Madeleine L’Engle wrote of this trade in an Epiphany poem, “One King’s Epiphany” –

I shall miss the stars.

Not that I shall stop looking

as they pattern their wild will each night

across an inchoate sky, but I must see them with a different awe.

If I trace their flames’ ascending and descending –

relationships and correspondences –

then I deny what they have just revealed.

The sum of their oppositions, juxtapositions, led me to the end of all sums:

a long journey, cold, dark and uncertain,

toward the ultimate equation.

How can I understand? If I turn back from this,

compelled to seek all answers in the stars,

then this – Who – they have led me to

is not the One they said: they will have lied.

No stars are liars!

My life on their truth!

If they had lied about this

I could never trust their power again.

But I believe they showed the truth,

truth breathing,

truth Whom I have touched with my own hands,

worshipped with my gifts.

If I have bowed, made

obeisance to this final arithmetic,

I cannot ask the future from the stars without betraying

the One whom they have led me to.

It will be hard not ask, just once again,

see by mathematical forecast where he will grow,

where go, what kingdom conquer, what crown wear.

But would it not be going beyond truth

(the obscene reduction ad absurdum)

to lose my faith in truth once, and once for all

revealed in the full dayspring of the sun?

I cannot go back to night.

O Truth, O small and unexpected thing,

You have taken so much from me.

How can I bear wisdom’s pain?

But I have been shown: and I have seen.

Yes. I shall miss the stars.

This is mercy – even when it seems harsh: “I cannot go back to night.” We cannot love what leads us to Jesus more than we love Jesus, any more than the Magi could love the stars that led their discovery more than the discovery itself. Who can cling to stars when they have seen the Daystar enfleshed? The stars didn’t lie; but the stars became insufficient. The kaleidoscope simply shifted, putting all their wisdom at the mercy of revelation.

You and I cannot go back to night, even if we love the minute adjustment of telescopes, the star charts, the constellations. Mercy will not let us. This is Epiphany: light to the Gentiles, God’s mercy in vivid form, appearing with ruthlessly consistent love.