Boundaries And Forgiveness by Aaron Perry

Jesus taught that if, when offering a gift to God at the altar, you remember a brother or sister has something against you, you should go and be reconciled and then return to offer your gift (Matt. 5:24). I get the impression that reconciliation is the gift God intends to give the worshipper—even before a gift has been brought to God.

Reconciliation is a complex subject because it involves three contexts: the offended, the offender, and the previous (or ongoing) relationship between the two. And reconciliation is so serious that if reconciliation is not forthcoming between two parties in the church, Jesus offered the resources of the family of faith and even his very presence to help (Matt. 18:15-20). Reconciliation is so important that Jesus put responsibility on both the offended (Matt. 18:15: “If your brother or sister sins,” with some manuscripts adding “against you”) and the offender (Matt. 5:23: “your brother or sister has something against you”) to seek reconciliation.

Is there a greater witness to the power of God than reconciliation? In an age of fast and loose friendship, of digital unfriending where one can “friend” without befriending, and when political candidates caused rifts between previously functional families and long-time friends, could a more courageous practice than reconciliation be imagined? As a Wesleyan, my hope in the ability of God to reconcile even the hardest of situations remains high; furthermore, as a Wesleyan, my appreciation for wisdom and practical theology runs deep. Reconciliation brings together hope and wisdom like no other challenge because reconciliation can take hard work and sometimes only happens over time.

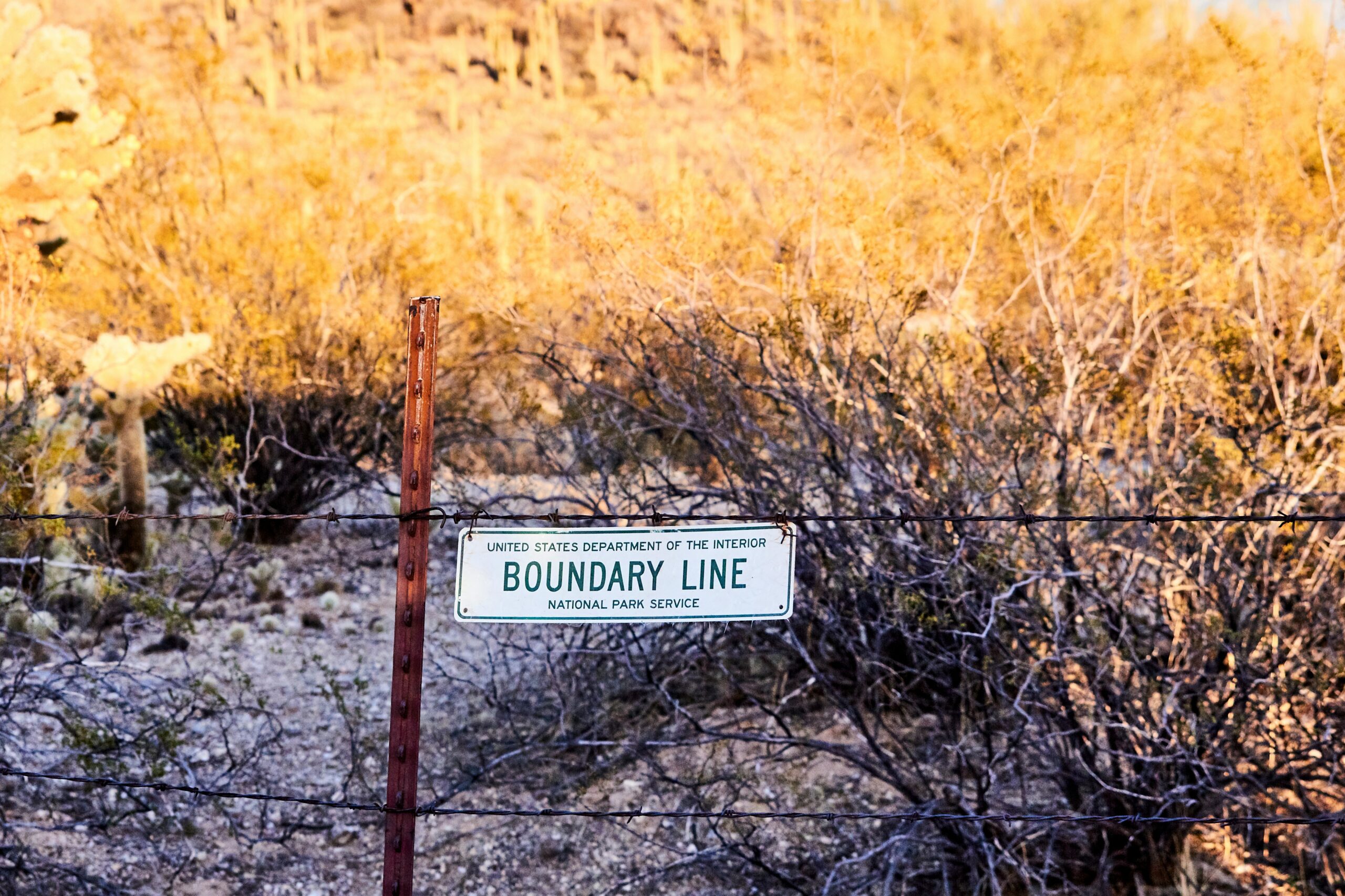

“Build the wall!” Perhaps the most memorable phrase of the 2016 election, it captured and made concrete the policy desire to increase border security and immigration regulation. It captured the imagination not only because it rolled much more easily off the tongue than typical policy speak, but also because it is something that each of us has been tempted to do: build walls in our own personal relationships. For our own emotional safety, we have constructed walls between ourselves and another and tightened regulations about when and how the other can (re-)enter our lives. But how do we connect this kind of personal “border security” with the call to be reconciled? How do we have boundaries while maintaining openness to be reconciled? OK. Let’s put away the political connotations for a bit. Let’s overlap this metaphor with a framework of forgiveness to see how it might help us understand boundaries and reconciliation.

Three Kinds of Forgiveness

Steve Sandage describes three different kinds of forgiveness1:

- Legal forgiveness: this forgiveness is an act of the will, allowing another to forego punishment. Sandage notes that in couples’ therapy, legal forgiveness might be a commitment to “bite one’s tongue”—not to respond with hostility or to be aggressive in arguing one’s side at every opportunity.

- Therapeutic forgiveness: Whereas legal forgiveness can be done instantly—and might be needed in an instant!—therapeutic forgiveness takes time. This is a place of healing for the offended. Without excusing the offense, the offended sees the offender in a new light and starts to bear empathy toward the offender’s own self and story. In this empathy and reconsideration of one’s story, there is healing.

- Redemptive forgiveness: This is the aim of the previous approaches to forgiveness. The full expression of forgiveness is reconciliation and redemption, so that God may transform our relationships not only with God but with each other.

Personal Boundaries

Before placing each category of forgiveness into the wall metaphor, let’s consider boundaries. We all have boundaries—invisible and visible lines inside of which we are safe and at ease. Some boundaries are very easy to identify. Skin is a physical boundary, so if you break my skin and I’m okay with it, then it’s likely that you’re a surgeon, nurse, or phlebotomist. (I don’t have a tattoo and don’t plan on getting one.)

Other boundaries are harder to determine and may be relative. Some people hug everyone, some people hug only a few, and some people don’t hug. Time boundaries are also relative. For example, it likely depends on your relationship for how long a person might spend at your house and not cross your boundaries. My mom has a phrase: “Fish and visitors stink after three days.” My guess is that if you’ve been a guest in my parents’ house and stayed longer than three days, then you’re either a really good friend or you’ve never been invited back.

We also have emotional boundaries. When another makes fun of something precious to our lives, overextends their help in a way that feels demeaning, or takes from us without asking, our emotional boundaries are crossed.

When boundaries are crossed, there is usually pain, but sometimes pleasure. Boundaries can be broached in ways that are exciting or comforting, such as when another extends into the beloved’s space to embrace or kiss or when deep knowledge of a person is used not to abuse, but to serve. For our purposes, I want to focus on when boundaries are crossed and there is discomfort and pain.

Boundaries should get marked definitively when there is pain at their crossing. A boundary might get marked by saying, “That makes me uncomfortable,” “That hurts my feelings,” or simply, “No.” Unfortunately, sometimes we do not mark boundaries and the offending person might continue to trespass boundaries without awareness or without care. When the unaware offender realizes there is a boundary, they might respect the boundary, but when the apathetic offender realizes there is a boundary, they will continue to break it over and over again. In these times, we must build a wall. Boundaries that will not be respected must be protected.

But just what kind of wall is built matters a great deal. Some walls (figuratively) are built with razor wire, spikes, armed turrets, and alligator-lined moats. These walls are dangerous. They are meant to be dangerous. They mark boundaries and warn the trespasser not to approach them—ever. They are weaponized walls: what was supposed to protect will be used to attack if given the chance.

Other walls are built with no less strength but are simply defensive. Rather than being lined with razor wire, they are lined with padding on the outside. When the offender comes close to the offended, they are not injured, but neither can they broach the wall. An attitude that seeks not to escalate ongoing conflict and not to react aggressively at any opportunity builds the padded wall.

Legal Forgiveness

Legal forgiveness is the padded wall. An attitude of legal forgiveness does not pretend that there is a functional relationship, but neither does it perpetuate the conflict. Legal forgiveness has marked boundaries and judged that what happened was wrong, but does not seek to attack given the opportunity.

Let’s put this back in Jesus’ teaching. Suppose you are the offended person who has built a wall. What might the offender find if they have left their gift at the altar to be reconciled to you? Will they be impaled on spikes? Nipped by the released hounds? Will the wall that is constructed become your weapon to inflict pain on them? It’s only a matter of time in life before any person needs to approach another for forgiveness and wonders what reception might be waiting for them.

Therapeutic Forgiveness

But why build walls at all? Like a surgeon cutting the same incision over and over again, when boundaries continue to be trespassed, there cannot be healing. When there are no walls and the wrong, unwanted, and/or misguided crossing of boundaries continues without correction, then forgiveness is simply not the right action. There can be no meaningful forgiveness in the midst of intentional, ongoing injustice.2 This is not to say that the offended, who in the case of ongoing injustice is powerless to achieve change, must harbor bitterness, angst, and frustration. It is only to say that that kind of grace and freedom is best described as gracious suffering, not forgiveness. The offended may be afforded a kind of emotional peace by God in the midst of ongoing injustice, but forgiveness is not the appropriate action.3

So, why build walls? We build walls on our boundaries in order to allow for healing. Walls built with legal forgiveness allow for therapeutic healing to happen behind them. They are meant to stop the offense so that the offended may recover, heal, and grow without worry that the offenses are going to continue unchecked.

Redemptive Forgiveness

Redemptive forgiveness recognizes that there is still ongoing work and opportunity even when boundaries are marked and healing has taken place. Forgiveness where injustice has ceased and therapeutic healing is taking place might still lead to reconciliation. Once there is healing, made possible by the wall, redemptive forgiveness allows for the crossing of boundaries once again, but with safety and security.

Let’s go back to Jesus’ command to leave our offering gift. The person who has left their gift at the altar and has encountered a padded wall now knows that a wall exists around the other person. Behind the padded wall, there is therapeutic healing taking place. Whether or not the time is right to access the door in the wall is unknown to the offender. Yet both offended and offender is called to aim at reconciliation. Again, whether or not reconciliation is possible in this life is very complex (and beyond the scope of one blog to address). But if both the offended and offender believe that following Jesus’ teaching is possible, then they must be aimed at reconciliation. This is redemptive forgiveness: doors and windows are added and walls may even be removed over time. The removal of the wall does not mean that boundaries no longer exist, but that a relationship may be marked by such safety, security, and trust that marking the boundaries with walls is no longer necessary. Redemptive forgiveness aims at the removal of walls, though it may start by opening doors and establishing guidelines for coming through the walls.

Conclusion

My first home left quite a bit to be desired—including central heat and about 200 square feet of exposed block in the basement. Given that I lived in Canada, building a wall to insulate the exposed block was one of my first projects. But I had never built a wall before. It remained daunting and mysterious to me—even with YouTube’s tutorials. Luckily, I had a willing and talented friend to help me frame and insulate a wall. The job was completed faster and better than it would have been on my own.

I think that’s how the walls we’ve talked about above are to be built: with the help of a friend. Unlike physical walls, it is sometimes easier to construct emotional walls on our own. Building walls with a friend helps keep us accountable to crafting the walls not as weapons but as protections. Friends help us make sure that walls mark our boundaries and don’t unnecessarily expand them. Friends who help us build walls can be given permission to see that there is healing work happening behind them.

1 Steven J Sandage and F. LeRon Shults, Faces of Forgiveness: Searching for Wholeness and Salvation; (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2003), especially Introduction and Section 1. While Sandage has deepened and modified some of the following, this thought is rooted in his taxonomy.

2 This is not to deny what peacemaking experts like Ken Sande might call “overlooking.” Healthy people can overlook an offense out of a sense of security and self. This ought not to be an ongoing action. Overlooking offenses is only possible by people with differentiated selves — people who have boundaries and know what they are. Overlooking the same offense either slips into a denial of the offense or is an indication that a person lacks a self and the ability to overlook an offense. In the latter case, they are not overlooking, but possibly being victimized or subjecting themselves to offense complicitly.

3 I owe part of this line of thinking to Fleming Rutledge, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans).