Elizabeth Glass Turner ~ The Narrative of Evil

Note from the Editor: At the time of original publication, Wesleyan Accent suspended its usual posting of a weekend sermon to reflect on the 2015 coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris, France.

Where haute couture fashion houses dominate and the Mona Lisa smiles, where the Notre Dame cathedral towers with long-held cultural memories of a famed hunchback and the Eiffel Tower beckons to retainer-wearing junior high tourists, where Rick and Ilsa looked out as the Nazis rolled in.

What is the true narrative of Paris, a very old city with a colorful history, the grand dame of Europe whose eyes twinkle as she alludes to youthful scandal?

What is the true narrative of Paris, where St. Thomas Aquinas studied, wrote and taught? The same Paris that boiled with blood during the French Revolution? The same Paris overtaken by the Third Reich? The same Paris scourged by the Black Plague? The same Paris now in a state of emergency with enforced curfew marooned in a nation whose borders have had to clang shut.

The true narrative of Paris is the narrative of any individual – at moments glorious, fallible, heartbroken, and exquisite.

Like the true narrative of Baghdad.

Or Damascus.

Recently Canon Andrew White, “the vicar of Baghdad,” alluded to his chiaroscuro life.

They were coming for him and his people. Friends were being killed or fleeing for their lives. So Andrew White did what he always does when faced with an enemy. “I invited the leaders of Isis [Islamic State] for dinner. I am a great believer in that. I have asked some of the worst people ever to eat with me.”

This extraordinarily self-confident priest is best known as the vicar of Baghdad, leader of a church in the chaos outside the protected Green Zone. He made his offer last year as the terrorist forces threatened to take the city. Did he get a reply?

“Isis said, ‘You can invite us to dinner, but we’ll chop your head off.’ So I didn’t invite them again!”

And he roars with laughter, despite believing that Islamic State has put a huge price on his head, apparently willing to pay $157m (£100m) to anyone who can kill this harmless-looking eccentric. Canon White was a doctor before he became a priest and could be one still, in his colourful bow-tie and double-breasted blazer with a pocket square spilling silk. But appearances are deceptive.

For the last two decades, he has worked as a mediator in some of the deadliest disputes on Earth, in Israel and Palestine, Iraq and Nigeria. He has sat down to eat with terrorists, extremists, warlords and the sons of Saddam Hussein, with presidents and prime ministers.

White has been shot at and kidnapped, and was once held captive in a room littered with other people’s severed fingers and toes, until he talked his way out of it. He is an Anglican priest but was raised a Pentecostal and has that church’s gift of the gab.

Canon Andrew has served as a voice from a region that we skim over in the headlines because it troubles us. But something that troubles you will eventually force its way into your consciousness, like a lump you want to ignore or the scrabbling of a mouse across the floor in the night.

Damascus, Baghdad, Paris.

What next? Miami, Atlanta, Boston? How might the narrative of more cities morph under the influence of evil? Paris is closer to the Western world than Damascus or Baghdad are in many ways. The American Statue of Liberty was a gift from France. French thinkers and writers have influenced intellectual development over the past few centuries. Our language is dotted with vocabulary we don’t think twice about because we don’t pronounce it in proper nasal fashion, but chaperone, restaurant, coup de grace – all these illustrate the invisible ties that stretch like cords across Atlantic waves. And so we sit up and take notice when Paris is beaten up and left bloodied on the roadside more than we do when Damascus and Baghdad are kidnapped and held for ransom.

Canon Andrew does not underestimate the strength of the evil that has been brutalizing Iraqis, Syrians, and now Parisians.

So what is to be done? “We must try and continue to keep the door open. We have to show that there is a willingness to engage. There are good Sunni leaders; they are not all evil like Isis.”

But surely there is only one logical conclusion to be drawn? He sighs, and answers slowly. “You are asking me how we can deal radically with Isis. The only answer is to radically destroy them. I don’t think we can do it by dropping bombs. We have got to bring about real change. It is a terrible thing to say as a priest.

“You’re probably thinking, ‘So you’re telling me there should be war?’ Yes!”

I am shocked by his answer, because this is a man who has risked his life many times to bring peace.

“It really hurts. I have tried so hard. I will do anything to save life and bring about tranquillity, and here I am forced by death and destruction to say there should be war.”

White had to be ordered to leave Baghdad at Christmas by his close friend the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Rev Justin Welby.

Evil is not the narrative of terror: terror is the narrative of evil. That which destroys for destruction’s sake; that which desecrates for desecration’s sake; that which relishes in inflicting suffering for suffering’s sake; that which forces death unannounced for death’s sake – this is the nature of evil.

And destroying for destruction’s sake, desecrating for desecration’s sake, inflicting suffering for suffering’s sake, forcing death for death’s sake – this leaves paralyzing fear in its wake, the kind of dry-mouthed, helpless terror that watches in vivid slow motion. This leaves night terror in its wake, thrashing in blankets from flashbacks. This leaves fear in its wake, the kind that bars windows and triple-checks locks, the kind that huddles in groups and squints in suspicion.

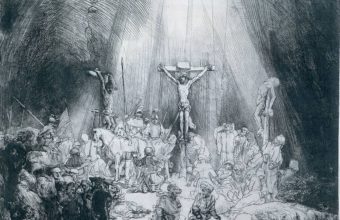

David wrote of this anguish in Psalm 22, and while it’s often read through the lens of the crucifixion of Christ, it also stands on its own, as his own distress:

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from saving me,

so far from my cries of anguish?

My God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer,

by night, but I find no rest.But I am a worm and not a man,

scorned by everyone, despised by the people.

All who see me mock me;

they hurl insults, shaking their heads.

“He trusts in the Lord,” they say,

“let the Lord rescue him.

Let him deliver him,

since he delights in him.”My heart has turned to wax;

it has melted within me.

My mouth is dried up like a potsherd,

and my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth;

you lay me in the dust of death.Dogs surround me,

a pack of villains encircles me.

There is no shame in feeling fear, or sorrow, or terror. There is no shame in shaking with grief, and loss, and shock. There is no shame in finding your mind paralyzed, your heart numb, your eyes glazed. No, there is no shame in bolting awake in the dark night with your heart pounding.

But in the midst of fear, grief, paralysis, and panic, there remains a quiet, immovable promise – the kind of promise that doesn’t erase suffering, but buys it out and remodels it. This hushed promise of granite-like solidity transcends laughter, happiness, and joy. It includes hope but exists outside of your ability to hope. Truth exists outside of your ability to feel happiness.

David finishes his song like this:

All the ends of the earth

will remember and turn to the Lord,

and all the families of the nations

will bow down before him,

for dominion belongs to the Lord

and he rules over the nations.

All the rich of the earth will feast and worship;

all who go down to the dust will kneel before him—

those who cannot keep themselves alive.

Posterity will serve him;

future generations will be told about the Lord.

They will proclaim his righteousness,

declaring to a people yet unborn:

He has done it!

No one can obliterate the future. No one can obliterate your life so completely that it is irredeemable. This is the truth that was not burned up in the furnaces of death camps. It cannot be buried in a mass grave. It can’t be executed at a concert or detonated at a soccer game.

Oh, the promise that trumps the narrative of evil. Oh, the promise that takes our sweaty palms in its hands.

We are not at the mercy of terrorists. They are at our mercy as we live in flesh and blood and bone the loving mercy of Jesus Christ, Emmanuel-God-With-Us, who was and is and is to come. As the orange-suited martyrs cried to Jesus on their sandy beach deathbeds, evil crumpled. They have no power over Jesus Christ, they have no power over the world to come, they have no power over your soul.

And so today we do not pray first and foremost for safety – as if it could be achieved in this life anyway. We pray for God’s will to be done on earth as it is in heaven. We pray for boldness and courage. We pray for peace, for healing, for comfort, for hope. We pray for faithfulness, for wisdom, for vision. We pray for Spirit-led choices, for grace, for redemption. And we pray for those who blow themselves up, kill other people, threaten and bully, remembering the Apostle Paul, who, before he met Christ, harassed believers and breathed murderous threats against them.

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Lord, have mercy.

And root out the sneaking parts of my own soul that wish harm on others, flare up in anger, or belittle my valuable fellow humans. For we all stand in need of the mercy of Jesus Christ.